American Empire: The U.S. Has Wanted War in Iran for a Long Time

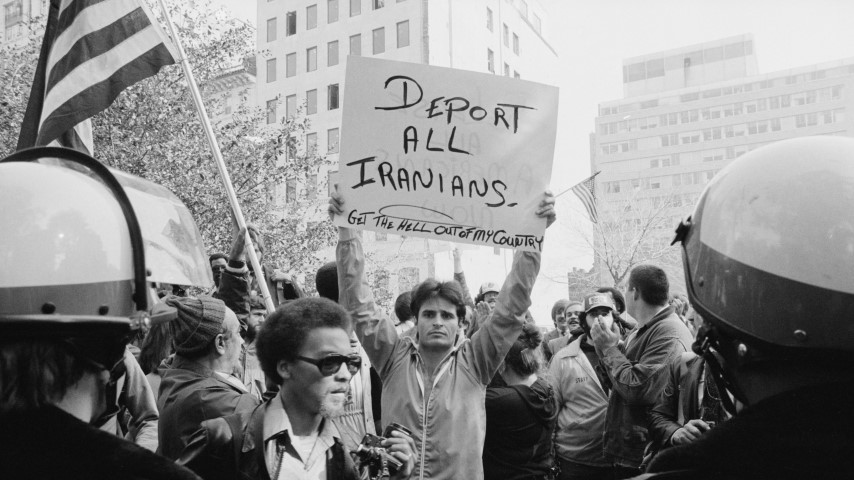

Marion S. Trikosko, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is American Empire, Splinter’s rolling series of articles exploring the power of the United States and the different ways it unleashes it upon the world. Read our other entries here.

Will the United States be dragged into another war in the Middle East? This has become the burning question of our time: might America, beholden to the whims of Israel, be forced, unwillingly, to step in on the side of its ally to face down Iran, with the possible consequence of sparking World War III and a nuclear apocalypse? It is a sickening prospect, to be sure, but the term “dragged” seems to be doing rather a lot of work there.

Over the course of the last year of perpetual Israeli atrocities, the U.S. has provided its ally with billions of dollars in military aid while bombing the Houthis in Yemen in defense of Israel. It has sent over horrifyingly powerful bombs, artillery shells, tank rounds and small arms to be used against, among others, thousands of children. It has deployed several thousand more of its own troops to the region, provided intelligence to Israel, and the U.S. has spread Israeli lies and propaganda at every turn. America repeatedly blocked demands for a ceasefire at the United Nations while trying to redefine the term ceasefire.

The United States has not been “dragged” into anything. It has been a willing partner in this spiraling war since day one, fought against Iran’s proxies in Gaza and Lebanon.

But things can get worse. The drums of war are beating, as the neocons, having once again found their confidence, are stirring shit more vigorously, calling for war in a faraway place they know nothing about. “We absolutely need to escalate in Iran,” as the headline of a recent Bret Stephens op-ed in The New York Times put it, elucidating the thinking of hawks on both sides of the aisle, Democrat and Republican alike. These bloodthirsty freaks, so detached from the death that war actually entails, fantasize about “reshaping the Middle East,” destroying Iran as we know it and creating a new state to America’s, and Israel’s, liking. Maybe this time, unlike in Iraq or Afghanistan, it may work?

The toppling of Iran’s theocratic regime would, in the minds of such dead-eyed imperialists, right the supposed wrongs of America’s failure to deal with the Islamic Republic since its founding. The two nations have long been sworn enemies, doomed to a cycle of animosity which may come to overwhelm the Middle East and possibly the world, but it wasn’t always so. There was a time when a previous Iranian regime was the darling of U.S. leaders.

Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi came to power in Iran in 1941. Sitting at the top of a constitutional monarchy, he enjoyed a great deal of power, but was tempered somewhat by an active parliament. The Shah was viewed as a vital ally by the Truman administration, who, within the context of the coming Cold War, coveted a friend in the region to resist the Soviet Union.

But he came to be despised by his own people. The Shah allowed Iranian oil to fall under foreign control, selling it to companies from abroad, most notably the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, which we know today as BP. The company grew fabulously rich by extracting and exporting Iran’s oil, and, while it did pay royalties to the Iranian regime for the privilege, it paid more in taxes to Britain, which relied on its colonial plunder to help construct its post-war social welfare state.

The Shah’s naked betrayal of his people led to the rise of Mohammed Mossadegh, who, in 1949, was elected prime minister on the promise of nationalizing the Iranian oil industry. The British, and their American allies, were not pleased when he actually followed through, and they began to plot his downfall. The countries’ respective foreign intelligence services, MI6 and the CIA, organized a coup against Mossadegh’s elected government, bribing people to cause unrest on the streets and allow a right-wing general, Fazlollah Zahedi, to seize control of the government. Mossadegh was deposed, Zahedi installed as prime minister, and the Shah empowered to rule as a dictator.

The CIA has since admitted to its role in the coup, while the U.K. has never officially acknowledged its own part in what happened.

The Shah, in the wake of the coup, reversed the nationalization of the oil industry, much to the delight of the primarily British and American companies that then flooded into the country, while also imposing, through violent means when necessary, a program of aggressive liberalization. He also spent billions on high-tech U.S. arms.

Opposition to the Shah’s authoritarian regime grew, with Ayatollah Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini emerging as a prominent critic. He, as a pious Shia leader, despised the Shah’s liberal programs on the grounds that they constituted the “Westoxification” of Iran. There were others in Iranian society that opposed the Shah not on religious or cultural grounds but because they plainly viewed him as a tool of Western imperialism. It was a synthesis of these forces, from the clergy to constitutionalist liberals to feminists to communists, that came together to overthrow the Shah in the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

Khomeini, after the Shah was overthrown, took power as the supreme leader of the new Islamic Republic. He moved quickly to consolidate his power, turning on the Iranian left that had helped the revolution succeed and imposing an authoritarian, violent state of his own. The Shah, meanwhile, fled to Egypt, before traveling to the U.S. to seek cancer treatment. The State Department, sensitive to the optics of this situation, apparently advised then-president Jimmy Carter not to permit the Shah’s presence on American soil, but Carter ignored the advice. Just as the State Department had feared, this was viewed with terrible suspicion back in Iran, with rumors swirling that the U.S. was again planning to reinstall the Shah in a coup. This paranoia is apparently what drove Iranian students, loyal to Khomeini, to take over the U.S. embassy in Tehran in November 1979 and to hold 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage there for 444 days.

The Iran hostage crisis marked the beginning of a bleak new phase in the shared history of Iran and the United States. Diplomatic relations between the two nations were severed, never to be reestablished, and U.S. sanctions were imposed on Iran for the first time. The mutual hatred only intensified after the U.S. threw its weight behind Saddam Hussein’s Iraq as it invaded Iran in 1980. Over the following eight years of war, America provided Saddam with weapons, military intelligence, and credit, even though they knew he was using chemical weapons.

Tensions flared again in 1983, when a suicide attack on a U.S. marine barracks in the Lebanese capital of Beirut killed 240 American service personnel. The attack was linked to Hezbollah, which, as we hear every day in the news today, is backed by Iran, so, the following year, the U.S. classified Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism for the first time, a designation that brings sanctions with it.

As the specter of Iran obtaining nuclear weapons came to dominate American leaders’ fears, the weapon of sanctions came to be wielded even more harshly. The Clinton administration imposed them, while George W. Bush, in the wake of 9/11, upheld them as he ratcheted up the rhetoric by describing Iran as part of the “Axis of Evil.” Some people in Bush’s administration, such as his vice president and present-day Kamala Harris supporter, Dick Cheney, were actively arguing for military intervention, which, Bush later admitted, he considered. While no war was launched, the sanctions continued to strangle the Iranian economy right through the early years of the Obama administration.

Sanctions, if anything, have strengthened the Iranian regime over the years, albeit to the detriment of the country’s people. As the Iranian economy has floundered, public welfare has been cut, wages weakened by inflation, and access to life-saving imported medications lost. Deaths of despair have soared, while public anger and resistance have been violently crushed by the regime, which, despite its failure to help its public, can nonetheless blame the U.S. for Iranians’ plight. Anti-American sentiment, for understandable reasons, has remained strong throughout the country.

Obama’s nuclear deal of 2015 did offer some hope that hostilities could soften with Iran, even as it was vehemently opposed by Israel, Saudi Arabia, and America’s own Iran hawks. The broad terms of the agreement established that, in exchange for an easing of sanctions, Iran would scale back its nuclear program, but the whole thing was destroyed when Trump came to power. Not only did he withdraw the U.S. from the deal in 2018, thus whacking more sanctions back onto Iran and encouraging it to again pursue its nuclear program, he brought the U.S. to the brink of war by having Iran’s most senior military figure, Qasem Soleimani, blown up in a drone attack.

War never materialized while Trump was in office, but tensions never really faded after he was succeeded by Biden. The nuclear deal was never revived, while the president’s total, unerring support for Israel’s increasing aggression has meant the possibility of war with Iran is with us once again. Biden has said publicly that he opposes an Israeli attack on Iranian nuclear facilities, but he has set “red lines” before and consistently permitted Netanyahu to cross them and face no consequences whatsoever. His word is worthless.

Biden’s presidency, in any case, is not long for this world, though neither of his potential successors represent much in the way of hope. After a first term in which he drove the U.S. to the precipice of war with Iran, it seems safe to presume de-escalation under Trump is unlikely, but Harris, too, has lately been offering up some worrying, hawkish rhetoric of her own, labeling Iran as the United States’ “greatest adversary.” While at this point it is difficult to predict what her foreign policy might actually look like, the signs are that, at best, it will resemble Biden’s.

Put plainly, it will be disastrous.

An American war with Iran is a catastrophe decades in the making. It may well be Israel that starts it, but the United States will bear responsibility for its perpetual meddling in Iranian affairs going back to the dawn of the Cold War. The Iranian regime today is an authoritarian theocracy that makes its people suffer, but that does not justify American aggression. There is a giddy hubris in the air today, with U.S. leaders and liberal commentators blinded by imperial arrogance. The hawks are soaring, and, should they get their wish, the Middle East, and maybe the world, will burn.