‘An Absolute Embarrassment’: COP29 Is Going Great

Photo by Vice-Presidência da República/Wikimedia Commons

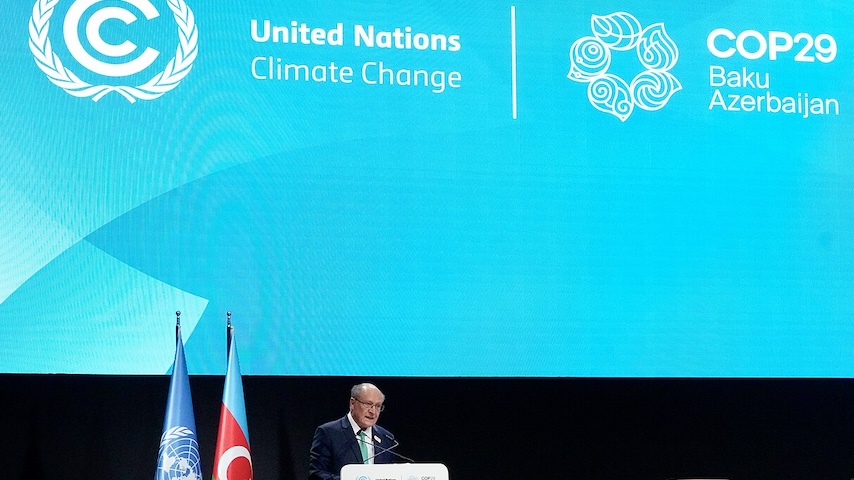

For much of the last ten days, the draft documents out of the U.N. climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan offered a smorgasbord of possible outcomes. The primary goal, an international climate finance target at least marginally in line with the extreme costs the developing world is facing, seemed far off — activists and those poor countries were calling for a number in the trillions, while the rich countries that would provide it dithered about their responsibilities. On Friday, the official last day of COP29 (most of these go into overtime), a draft with an actual number emerged: $250 billion per year from rich to poor, by 2035.

“This text is an absolute embarrassment. It’s the equivalent of governments handing the keys to the firetruck to the arsonists,” said Laurie van der Burg, the global public finance manager for Oil Change International, according to the Guardian. This sentiment is widespread: “The climate finance text is completely inadequate,” said Stephen Cornelius, WWF’s deputy global climate and energy lead. “The amount is far too low, and rich countries don’t even commit to delivering all of it.” Another observer called the target “incredibly weak.” Various negotiating blocs have all criticized it; no one is happy.

The draft text actually includes two numbers, that $250 billion figure as well as an aspirational goal of $1.3 trillion. The difference lies in the boring legalese and tortured prepositional phrases that plague all multilateral agreements, as the text “calls on all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing” toward the higher number. In contrast, it “decides to set a goal” of $250 billion.

And then there are the subheadings and caveats. The money — even that smaller number, well below the consensus dollar figures that the developing world actually needs in the face of a rapidly warming world — should come “from a wide variety of sources, public and private,” which in practice means a lot of it would be interest-bearing loans that will only help lock poor countries into an ongoing debt cycle that keeps them poor and their supposed benefactors rich.

The timing also sucks. The previous finance pledge of $100 billion annually was made way back in 2009, and rich countries even struggled to meet that mark. Scaling up to a grossly inadequate number after ten more years of increasingly dire climate change impacts feels like insult to injury at this point.

“We know rich countries can pay up the trillions they owe to the Global South by ending fossil fuel handouts, taxing the super rich, and changing unfair global financial rules,” van der Burg said. “We need a dramatic change in direction if we want a fighting chance to leave Baku with a finance deal that can support the fair fossil fuel phaseout that we need to avoid breaching 1.5°C.”