Heat Deaths in the U.S. Were Dropping Slightly Through 2016. That Trend Is History.

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images

Heat-related deaths are complicated. They don’t just track linearly with temperature; there are inputs relating to the availability of air conditioning, to public health messaging and outreach, to localized laws guiding outdoor work, and just to a given area’s familiarity with the issue. But also: if it just gets too hot, people will die.

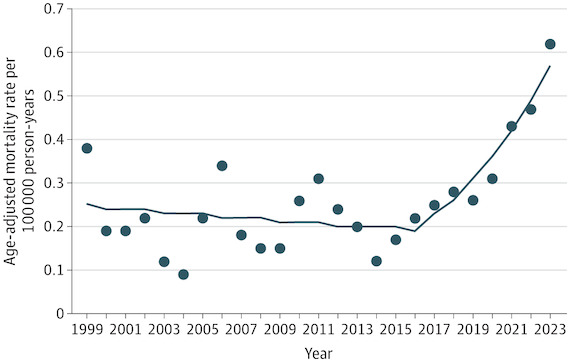

A study published Monday in JAMA bears all this complexity out: It confirms a previously observed trend of heat deaths actually decreasing in the first part of this century, and then quantifies an abrupt about-face since 2016, when mortality started rising in alarming fashion along with the mercury.

“As temperatures continue to rise because of climate change, the recent increasing trend is likely to continue,” wrote study authors from UT San Antonio, the University of the Health Sciences School of Medicine, and Penn State. They used data from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention database, and found a total of just over 21,500 heat-related deaths in the U.S. between 1999 and 2023; that’s good for an “age-adjusted mortality rate” of 0.26 per 100,000 person-years.

Across that full quarter-century study period, the absolute number of deaths jumped by over 100 percent — from 1,069 deaths in 1999 to 2,325 in 2023, representing a 63 percent increase in the rate of deaths. But this increase was not smooth: between 1999 and 2016, the rate actually dropped by about 1.4 percent per year — this was not a statistically significant change — before shooting upward by almost 17 percent each year from 2016 through last year. That trend very much is statistically significant.

This mirrors some other data. A 2020 study found similar decreases in heat-related mortality risk for several decades through 2018, a trend the authors said could be due to “improved messaging and increased awareness.”

Meanwhile, while the overall warming curve is relatively stable over the past four or five decades, there has undoubtedly been a recent uptick: the warmest 10 years on record are the last 10 years we have lived through, culminating in 2023’s warmest year “by far.” Other studies suggest we could all be in for some truly devastating summer seasons very soon: one 2023 study found that the heat deaths in a year considered a 1-in-a-100 extreme event in 2000 could be expected every 10 to 20 years by 2020. That figure will drop further as we cross an average of 1.5 degrees C and 2.0 degrees C of warming, and what was once considered an unlikely outlier will just be “summer.”

There is still a lot of noise in this sort of data though, including with the new study. To tally up the heat-related deaths, the researchers looked for three specific codes used in the database — codes corresponding to “environmental hyperthermia of newborn,” “effects of heat and light,” or “exposure to excessive natural heat” as either the underlying or contributing cause of death. The problem is that heat-related mortality can often just look like mortality of some other common cause — heart problems or breathing issues, say — and different states, counties, and even countries have wildly different ways of recording those causes. The authors of the new study say their work is limited by potential for misclassification which could yield underestimates, as well as by increasing awareness biasing results in the other direction, and by undercounting among particularly vulnerable groups of people.

Still, the basic message is undoubtedly true: it’s getting much hotter, and more people are dying as a result. Those in charge should be taking note, the study authors wrote: “Local authorities in high-risk areas should consider investing in the expansion of access to hydration centers and public cooling centers or other buildings with air conditioning.” In the U.S., that message is getting out, including with the recent release of a National Heat Strategy aimed at reducing extreme heat’s impacts. Almost all heat-related deaths are preventable, with better policy and infrastructure in place; time to get started.