How Does the World Respond to Syria Now?

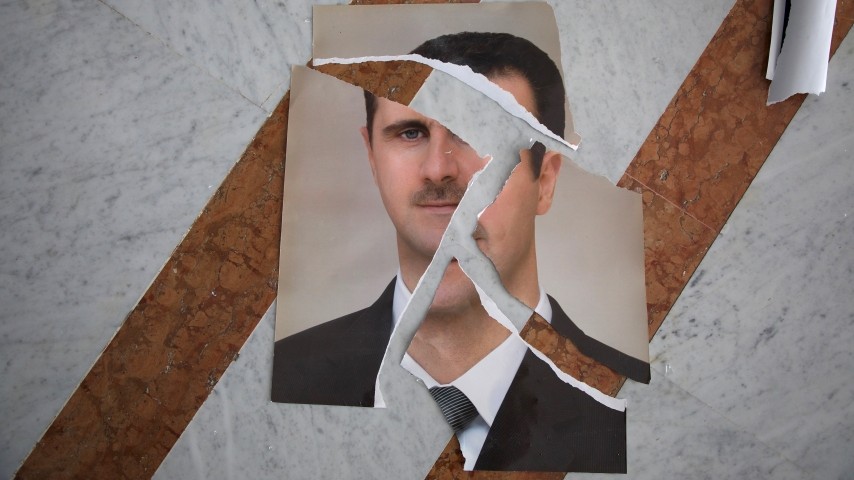

Photo by Ali Haj Suleiman/Getty Images

This week, Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), one of the key rebel groups that toppled President Bashar al-Assad, named a new interim prime minister. Mohammad al Bashir said he would lead a caretaker government until March 2025 and “until the constitutional issues are resolved.”

Bashir did not specify exactly what those constitutional issues were, but Syria faces a daunting few months ahead. After 13 years of civil war, rebel groups deposed Syria’s dictator after a shock offensive led by HTS, an Islamist militia whose leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, broke with Al-Qaeda in 2016. HTS took nominal control of a divided country with many disparate groups and competing armed factions and a population facing dire humanitarian and economic crises. The jubilation over Assad’s collapse could not fully overshadow the incredible uncertainty hanging over Syria’s future.

This also pushes the rest of the world into a very dicey situation: how to handle HTS, which is designated as a foreign terrorist organization by the United States, the United Nations, and many other countries.

The HTS terrorist designation has been in place for years, but the classification has a new urgency. It makes it harder for Syria’s new leaders to engage in out-in-the-open diplomacy and access critical financial resources. Syria itself remains under heavy sanctions. Even with exceptions for humanitarian aid, it makes the kinds of investments any government would need to restore basic services, rebuild the country, and resurrect and reconnect the economy extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible, to obtain. If any interim government lacks the capability to start addressing even some of these challenges, it may quickly jeopardize Syria’s fragile stability and any chance the country has toward a peaceful transition.

“That is the dilemma that the international community is facing now: do we move quickly and then end up regretting it and empowering malign actors? Do we act too slowly, too cautiously? But that might also have the same effect,” said Jasmine El-Gamal, a Middle East analyst and former Pentagon advisor.

HTS has distanced itself from jihadist groups, and Jolani, its leader, has tried to downplay its radical roots. The group has made overtures to religious minorities. But in the parts of Syria that HTS has controlled, its civilian government has been anything but democratic. The administration in Idlib has cracked down on protesters and journalists. Syria’s new interim prime minister, Bashir, was the head of the Salvation Government, the administration in northwest Syria controlled by HTS. Bashir’s appointment was an early, worrying sign of the potential authoritarian direction of this HTS-led Syrian government.

“My main concern with HTS, though, isn’t ideology, it’s the dictatorial practices, which they haven’t given up any of those in Idlib over the last five years,” said Charles Lister, senior fellow and the Director of the Syria and Countering Terrorism & Extremism programs at the Middle East Institute.

“HTS is not going to be making peace with al Qaeda and ISIS anytime soon, but I am concerned about their dictatorial nature,” Lister added. “Early signs in Damascus are good in the sense that it’s stable, but they’re not good in the sense that the transition is being entirely led only by this group, and that’s the big challenge lying ahead.”

The U.S. and other partners have floated the possibility of delisting HTS as a terror group, although that is not a process that can happen instantly. There is a recognition of the dire situation Syria faces, but also of the opportunity to forge something new after decades of dictatorship under Assad and the horrors of more than a decade of war. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said this week that the U.S. would be willing to “recognize and fully support” a Syrian government if the transition process “should lead to credible, inclusive and nonsectarian governance that meets international standards of transparency and accountability.” Other countries and the United Nations’s envoy to Syria have made similar statements.

But HTS’s overtures are just that right now – signals, but not commitments to a pluralism, and its current track record is not exactly reassuring. But HTS also wants international legitimacy and recognition, and the terrorism designation does offer leverage to influence the new Syrian government to fulfill some of the promises.

“The international community should have a clear position on how to engage, what to use that leverage for, and how to ensure that what’s happening in Syria is not led by HTS, but is done in a way that represents the ambitions and demands of the Syrian people collectively,” said Haid Haid, an expert on HTS and a consulting fellow with Chatham House.

Few think this will be a straightforward or immediately successful process. HTS is the key rebel group right now, but it is far from the only one in Syria. Other armed groups have interests and regional centers of power. Rebel fighters and opposition forces from the Druze minority in Syria’s south joined the fight to defeat Assad, and were among the first to reach Damascus. Then there are the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the Kurdish group that partnered with the U.S. to help defeat ISIS and governs the autonomous northeast of the country. The SDF has said it has a deal with the HTS, and will send a delegation to Damascus. Kurdish forces also raised Syria’s revolutionary flag, used by the opposition forces since 2011, in a gesture of solidarity. But the SDF is also under pressure from other militias, including the Syrian National Army; Turkey is backing that ragtag opposition coalition in order to undermine the SDF’s influence in northeastern Syria. Those two groups have engaged in serious clashes, though they just reached a ceasefire in Manbij, a site of heavy fighting in the days after Assad’s fall.

These tensions will not disappear, and all of these parties will seek influence or a stake in any Syrian future. The test for HTS will be whether now, closer to power than ever, it will willingly find ways to share it around, or if it will seek to further consolidate control. “It’s easier to send all of the right signals amidst the euphoria of liberation and freedom. It will be a lot harder to keep those signals going once HTS starts to be challenged by minority groups and be issued demands by minority groups,” Lister said.

Lister added that engagement, rather than isolation, was probably the best strategy here. But again, this is a precarious balancing act.

Syria is not a neat narrative. A tangle of rebel groups, of varied political and religious extremes, finally ousted Assad, rather than some ideal version of a pro-democratic resistance. But all of those parties, HTS included, should get a chance to evolve and work out the transition for Syria. So should the civil society leaders, activists, and civilians in Syria and abroad who have been envisioning a democratic future for Syria for years. That process will potentially be messy and ugly and veer from the Western playbook of perfect political process – which actually has a pretty terrible track record anyway. The U.S. and the international community can and should condition things like sanctions relief on seeing real moves toward protections for minorities or commitments to human rights and rule of law. But it also should keep back channels open for engagement, and consider ways to give the transition some cushion to figure it out, including by ensuring unfettered access to humanitarian aid.

The U.S. and its partners will also have limited influence in the outcome in Syria. In the past decade, other regional and other international players have vied for power and influence in Syria – often to the detriment of the Syrian people. But they are not just going to dip out of Syria quietly.

Turkey looms large, and it is actively exerting its influence through its close alignment with rebel groups in Syria, including HTS and the Syrian National Army, largely as a counter to Kurdish influence and power in Syria. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has a stake in a stable Syria, one that will allow the millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey to return.

Russia propped up Assad’s regime, and his defeat is an embarrassment to Vladimir Putin’s global ambitions. Moscow is unlikely to completely abandon its entire Syria investment, and has reached out to HTS, including to protect some of its military assets. Assad’s defeat is another blow to Iran’s axis of influence after a series of them this year. Israel is expanding into Syria, and has launched around 350 strikes on military sites and alleged chemical weapons stockpiles facilities in recent days. Israel has called these actions preemptive, but their goals are not entirely clear, though these are exactly the kind of destabilizing actions that would quickly upset a delicate and shaky government transition process.

The United States, too, has conducted bombing campaigns against ISIS targets in Syria, which it says is in an effort to prevent a resurgence of the terror group in a power vacuum. Incoming President Donald Trump has said Syria is not the U.S.’s problem, but it will be up to his administration to determine what to do with the 900 U.S. troops still stationed there – and, likely, how to treat HTS.

Perhaps the worst outcome for Syria would be another version of outside powers picking a side and vying for control. That’s fundamentally why allowing and empowering a Syrian-led process is so critical, as it may buffer attempts at outside power grabs.

None of this is a guarantee for success, but Syria does have a real chance to chart an entirely new future after half a century of oppression and conflict. The first step, said El-Gamal, “is just listening to Syria, and to those Syrian voices, particularly those who’ve been involved in these political negotiations, in that political process, over the last decade.”