How Fossil Fuel Money Made Climate Change Denial the Word of God

In 2005, at its annual meeting in Washington, D.C., the National Association of Evangelicals was on the verge of doing something novel: affirming science. Specifically, the 30-million-member group, which represents 51 Christian denominations, was debating how to advance a new platform called “For the Health of a Nation.” The position paper—written the year before An Inconvenient Truth kick-started sense of public urgency around climate change—included a call for evangelicals to protect God’s creation, and to embrace the government’s help in doing so. The NAE’s board had already adopted it unanimously before presenting it to the membership for debate.

At the time, many in the evangelical movement were uncomfortable with its close ties to the Republican anti-environmental regulation agenda. That year, a group called the Evangelical Alliance of Scientists and Ethicists protested the GOP-led effort to rewrite the Endangered Species Act, and the NAE’s vice president of governmental affairs Richard Cizik pushed for the organization to endorse John McCain and Joe Lieberman’s cap-and-trade bill. “For the Health of a Nation,” which Cizik also pushed, was an opportunity to draw a bright line between their support of right-wing social positions on abortion and civil rights and a growing sentiment that God’s creation needed protection from industry.

“Evangelicals don’t want themselves identified as the Republican Party at prayer,” the historian and evangelical Mark Knoll said at the time in support of the platform.

He was wrong. The rank-and-file membership rejected the effort. Like the oil and utilities industries, they decided that recognizing climate change was against their political interests.

At the behest of a group called the Interfaith Stewardship Alliance, the board buckled, releasing a statement in February 2006 “recognizing the ongoing debate” on global warming and “the lack of consensus among the evangelical community on the issue.” Just days later, an outside group of 86 evangelical leaders, under the aegis of the Evangelical Climate Initiative, issued a “Call to Action” declaring that climate change was real and that “millions of people could die from it in this century.”

Conservative groups, funded by fossil fuel magnates, spend approximately one billion dollars every year interfering with public understanding of what is actually happening to our world.

For his trouble, Cizik was targeted by a collection of hard right Christians, who petitioned the NAE board to muzzle him or force him to resign. “Cizik and others are using the global warming controversy to shift the emphasis away from the great moral issues of our time, notably the sanctity of human life, the integrity of marriage, and the teaching of sexual abstinence and morality to our children,” their letter read. It also implied that Cizik, who had worked for the NAE for nearly three decades, supported abortion, giving condoms to children, and infanticide.

The NAE didn’t silence Cizik, but it didn’t take up his cause, either. (Ultimately, his undoing was not climate change, but same-sex marriage. “I would willingly say that I believe in civil unions,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross in May 2007. “I don’t officially support redefining marriage from its traditional definition, I don’t think.” He was fired ten days later.)

The NAE did eventually endorse climate action in 2015. But it was too late. By that time, a corps of right-wing Christians, funded by fossil-fuel interests, had hijacked the public and political machinery of the evangelical movement. They are now in the White House, where the anti-environmental agenda is dominated by Christian fundamentalists like EPA Commissioner Scott Pruitt while the more moderate views of former ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson are ignored. This is the story of how they did it.

At a town hall in Michigan last May, Republican Rep. Tim Walberg assured his constituents that, while the climate may be changing, they don’t need to be concerned. “As a Christian, I believe that there is a creator in God who is much bigger than us,” he told them. “And I’m confident that, if there’s a real problem, He can take care of it.”

This idea—that whatever happens in God’s creation happens with His blessing—has deep roots in the American evangelical community, especially among the elite fundamentalists who walk the halls of power in Washington, D.C. For years, an evangelical minister named Ralph Drollinger has held weekly Bible studies for members of Congress, preaching that social welfare programs are un-Christian and agitating for military action against Iran. (In December 2015, he expressed his desire to shape Donald Trump into a benevolent, Christian dictator.) Drollinger also teaches that climate change caused by humans is impossible in light of God’s covenant with Noah after the Flood: “To think that man can alter the earth’s ecosystem—when God remains omniscient, omnipresent and omnipotent in the current affairs of mankind—is to more than subtly espouse an ultra-hubristic, secular worldview relative to the supremacy and importance of man,” he wrote recently.

Conservative groups, funded by fossil fuel magnates, spend approximately one billion dollars every year interfering with public understanding of what is actually happening to our world. Most of that money—most of the fraction of it that can be tracked, anyway—goes to think tanks that produce policy papers and legislative proposals favorable to donors’ interests, super PACs that support politicians friendly to industry or oppose those who are not, or mercenary lobbyists and consultants, in some instances employing the same people who fought to suppress the science on smoking. In terms of impact, however, few investments can rival the return that the conservative donor class has gotten from the small cohort of evangelical theologians and scholars whose work has provided scriptural justifications for apocalyptic geopolitics and economic rapaciousness.

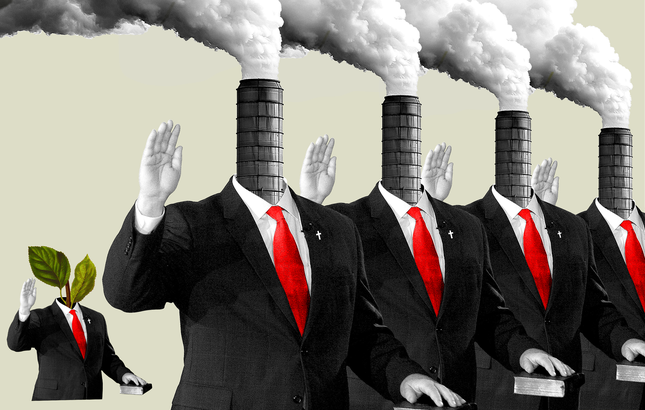

The Cornwall Alliance is an enforcer, stifling dissent in the evangelical community, smothering environmentalist tendencies before they gain a following.

“Throughout the history of the church, people have always found ways to use God and scripture to justify empire, to justify oppression and exploitation,” Kyle Meyaard-Schaap, an organizer with a pro-environmental Christian group called Young Evangelicals for Climate Action (YECA), told me. “It’s a convenient theology to hold, especially when we are called to drastic, difficult action.”

Many of these soothsayers are gathered together in an organization called the Cornwall Alliance—formerly known as the Interfaith Stewardship Alliance, the same group that mobilized against Cizik’s environmental proposal—a network with ties to politicians and secular think tanks across the conservative landscape. In 2013, Cornwall published an anti-environmentalist manifesto called Resisting the Green Dragon. “False prophets promise salvation if only we will destroy the means of maintaining our civilization. No more carbon, they say, or the world will end and blessings will cease,” it warns. “Pagans of all stripes now offer their rival views of salvation, all of which lead to death.” Members of the Cornwall Alliance and their ilk are not simply theoreticians but enforcers, stifling dissent in the wider American evangelical community, smothering environmentalist tendencies before they gain a following.

The pull of fossil-fuel interests and the religious right is so strong that even conservative politicians who privately believe climate change is caused by humans have kept that view secret. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island, has said that he knows of at least a dozen Republicans in the Senate who accept climate science and want to take action, but feel they can’t do so for fear of the political repercussions—despite the fact that recent polling shows a majority of Republican voters believe that the United States “should play a leading role” on climate action. Half a dozen politically connected evangelical Christians who are active on Capitol Hill backed up Whitehouse’s claim to Splinter, saying they have either first- or second-hand experience with politicians who admit in private that they accept climate science even as they oppose regulations and reforms in public.

Bob Inglis, a former GOP congressman from South Carolina who lost his seat to a primary opponent during the Tea Party surge of 2010, told Splinter that there are Republican senators and representatives who want to take climate action but are “terrified” to do so. Reverend Mitch Hescox, president of the Evangelical Environmental Network, estimated that there are as many as 20 senators who would take action for climate and clean energy—but only if there were grassroots support to do so. Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech and an evangelical Christian who believes in climate change, suspects that the “vast majority” of those who dismiss climate science in Congress are secret believers. “We don’t have a lot of years for these people to come out of the closet,” Cizik, the ousted NAE board member, said.

Still, Inglis, Hescox, Hayhoe, and other evangelical Christians were not willing to expose the politicians who feel that climate action is simply too great a political risk. They fear that Republicans who are seen to support climate action, or even waver on opposing it, would immediately be subject to well-funded primary challenges by more ideologically committed candidates in the same way that Inglis was. “I don’t want to scare them off before I have the grassroots support for them,” Rev. Hescox told me.

The most prominent climate hardliner in the U.S. Congress is Sen. Jim Inhofe. “Senator Inhofe will take an act of God to be changed,” Rev. Hescox said with a laugh when I asked whether the Oklahoma politician would ever see the light. “That one’s in God’s hands, not mine.” In 2012, while promoting his book The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future, Inhofe told a Christian radio program, “God’s still up there. The arrogance of people to think that we, human beings, would be able to change what He is doing in the climate is to me outrageous.” In 2015, the Heartland Institute and the Heritage Foundation—two of the most influential and well-funded think tanks in the conservative political world—honored Inhofe with the Political Leadership on Climate Change Award. In his speech accepting the award, the then-chairman of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee lauded the think tanks, telling their members that they “are on the right side of the Lord on all of these things,” and that God “will richly bless you for it.”

Together, Cornwall, Heartland, and Heritage have been able to set the terms of the conservative conversation—evangelical or otherwise—about the climate.

Former Inhofe staffers and aides are flooding through leadership positions at the EPA, now led by Pruitt. About a month after Donald Trump took office, Drollinger began leading a weekly Bible study for members of the president’s cabinet. “It’s the best Bible study that I’ve ever taught in my life,” he told CBN News in a recent interview. “They are so teachable; they’re so noble; they’re so learned.”

A copy of Pruitt’s personal calendar, released by the EPA in response to Freedom of Information Act requests from Splinter and other outlets, shows that Pruitt began attending in mid-March. All visitors hosting events in congressional buildings need to be sponsored by a member of the House or the Senate. Drollinger’s Capitol Ministries boasts 49 sponsoring representatives (including Walberg, who is a graduate of evangelical Taylor University and Wheaton College) and eight sponsoring senators, including Joni Ernst of Iowa, who neither accepts climate science nor denies it outright, and Mike Rounds of South Dakota, who allows that the climate is changing but claims to feel that human activity is one small cause among many. Both Ernst and Rounds sit (with Inhofe) on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee; their offices did not respond to requests for comment.

Drollinger declined to be interviewed for this story, and a Capitol Ministries spokesperson wrote in an email that not all of the minister’s congressional sponsors share his views. In a 2015 interview with the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (of which he is a trustee), Pruitt said he believes that, under a proper reading of the Constitution, “government would be kept out of religion, not religion out of government.” At a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden announcing the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris agreement, Pruitt, in a linguistic nod to his fellow evangelicals, declared: “We owe no apologies to other nations for our environmental stewardship.” An EPA spokesperson insisted that any questions about the administrator’s religious views be submitted in writing, and stopped responding to emails after I did so.

“The greatest solution, if we did face a problem, which I don’t believe we do, is not central planning, is not putting U.N. bureaucrats in charge—it’s innovation and technology,” Marc Morano, a former speechwriter for Inhofe and prominent climate skeptic, told me. “If we really do face a crisis, the solutions will just happen naturally. You don’t need all this alarm. Whatever’s going to happen to address the problem, if there is a problem, is going to happen on its own.”

“There’s a wing of the evangelical church that’s historically distrustful of science and of modernity,” Meyaard-Schaap, the YECA organizer, told me, citing the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 and the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925. “This was a faction of the church that had been here for a while, who had significant cultural power and saw that power diminishing,” he said. “In the face of what they saw as significant threats to their identity, that wing of the church decided that their best reaction was to retreat, to pull away from public life, to invest in their own institutions, to calcify this resistance to modernity and science.”

This retreat lasted until the Reagan administration. In 1984, right-wing Christian leaders and theologians formed a group dubbed the Coalition on Revival for the express purpose not only of re-politicizing evangelicals but of guiding them towards a particular fundamentalist worldview. In its own words, the Coalition’s aim was to “influence, penetrate, and permeate” every aspect of society and to “rebuild civilization on the principles of the Bible.” To accomplish this, members of the Coalition sought “to take every thought captive to the obedience of Christ.”

As luck would have it, the “Christian World View of Economics” is avowedly business-friendly.

Over the course of the next two years, the Coalition—guided by Christian Reconstructionists like the influential R.J. Rushdoony, who believed that the United States should adopt Old Testament laws—staked out positions on the correct, Christian worldview on seventeen different spheres of human life, including government, law, the family, education, and science. A precocious young scholar named E. Calvin Beisner served as the group’s general secretary, helping to draft the “Manifesto for the Christian Church,” which was signed not only by religious groups like the Family Research Council and the Home School Legal Defense Association, but also by a Republican congressman, a representative from the National Republican Senatorial Committee, and a White House liaison. Beisner also chaired the Economics Committee, which ultimately produced a twenty-one page document detailing Christian positions on economic issues. In an email, Beisner confirmed that he still endorses both documents.

As luck would have it, the “Christian World View of Economics” is avowedly business-friendly, condemning any economic policy that would impede the enrichment of industrialists and financiers. “The root cause of all poverty—spiritual and material—is the Fall of man,” the paper proclaims. “The Bible and observation confirm that most poverty is due to disobedience to God’s laws by individuals and their societies.” The only way to deliver humanity from poverty, then, is to reshape society according to Christian doctrine—which, as the Coalition interpreted it, looks an awful lot like free-market capitalism.

In the decades since its publication, the coalition’s members have risen, fallen, and risen again in American politics. Beisner went on to found the Cornwall Alliance; one of the first Cornwall Declaration’s signers was Bill Bright—who was a mentor to the Trump Administration’s unofficial preacher Ralph Drollinger. “Cornwall doesn’t matter to your average politician, but it plays a very important role in buttressing evangelical resistance to climate action, or even acknowledging that climate change exists,” Bruce Wilson, researcher and co-founder of Talk to Action, told me in an email. “Evangelicals can point to the Cornwall Alliance as apparent evidence that there’s a broad coalition of conservative evangelical and fundamentalist academics and theologians who reject climate change science.” The group’s board of advisors has included a number of other Coalition on Revival alumni, including founder and director Jay Grimstead.

For almost 20 years, Beisner and members of the Cornwall Alliance have worked with establishment conservatives to bolster opposition to climate change: The Heartland Institute identifies him as a policy advisor on its web site, and he speaks regularly at the institute’s annual conference on climate change (though in an interview he curiously denied ever actually giving any policy advice to Heartland). The Heritage Foundation hosted the 2015 premier of Where the Grass is Greener, a documentary produced by the Cornwall Alliance. In May, Beisner and senior executives from Heartland, Heritage, and a slew of other billionaire-funded political entities like Americans for Prosperity and the Competitive Enterprise Institute sent a letter to Donald Trump urging him to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement and asking him to stop funding United Nations global warming programs.

Together, Cornwall, Heartland, and Heritage have been able to set the terms of the conservative conversation—evangelical or otherwise—about the climate. They determine what science is acceptable, which proposed solutions can be considered, and what the consequences of inaction might look like. “There’s a very strong connection between those institutions and the evangelical Right,” Rev. Hescox told me. “Their denial of the science—and really portraying this as a big government issue—is why there was so much pushback among evangelicals.”

The Cornwall Alliance, joined by scientists associated with organizations partly funded by ExxonMobil, continued hammering away at Christian groups that supported action on climate change. In 2008, it launched the bizarrely named “We Get It!” campaign, which targeted the Evangelical Climate Initiative and was endorsed by a slew of conservative organizations, including the Family Research Council and David Barton’s WallBuilders.

“The ‘We Get It!’ declaration speaks for me, and I believe it speaks for the vast majority of evangelicals, who are as tired as I am of being misrepresented by people who don’t bother to get their theology, their science, or their economics right,” Inhofe said in a statement. “Consequently, they put millions of the world’s poor at risk by promoting policies to fight the alleged problem of global warming that will slow economic development, and condemn the poor to more generations of grinding poverty and high rates of disease and early death.” According to journalist and historian Frances FitzGerald’s new book, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, the campaign was funded in part by Koch Industries.

In 2013, Cornwall (with assistance from the Heritage Foundation) launched the Resisting the Green Dragon campaign, which the sociologist Antony Alumkal calls “a case study in the paranoid style, using rhetoric that is extreme even by Christian Right standards in order to scare laypeople away from [environmentalism].” The campaign included both a book, written by physicist and “lay theologian” James Wanliss,” and a 12-part DVD series starring luminaries of the evangelical right, all laying out the case that green Christian movements are born of a “spiritual deception” that puts the needs of nature before people—a demonic worldview that requires an explicitly Christian response.

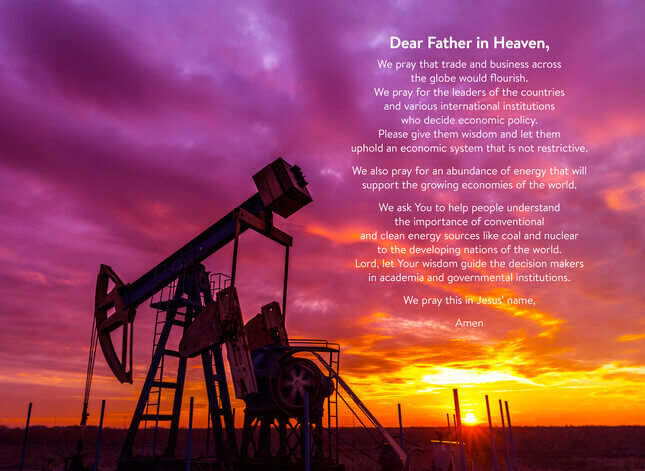

“History is…not a matter of fate, conservation, or man’s abilities, but of the decree of God,” Wanliss writes. “At the same time, God commands men to take dominion in the name of Christ, to fill the earth and multiply. This is not possible without a wholehearted embrace of Jesus Christ, on a global scale…Rather than seeking to save the planet on terms dictated by the Green Dragon, Christians ought to be preaching the only message that can save the planet—the gospel of liberty in Jesus Christ.”Recently, Beisner, a prolific writer equally comfortable deploying poststructural literary theory or Calvinist theology, has infused his rhetoric with even more fire and brimstone. “We are made in the image of the Creator. So we don’t have to leave nature as we found it,” he argued recently. “We can steward the earth to enhance its fruitfulness, beauty, and safety. And we can do it to glorify God and serve our neighbors.” In May, he described the climate marches as “thuggery—typical of communist movements from the French Revolution through the socialist revolutions of the 1840s and the Russian and Chinese revolutions.” A prayer for the free market economy published on the Cornwall website reads:

Dear Father in Heaven,

We pray that trade and business across the globe would flourish. We pray for the leaders of the countries and various international institutions who decide economic policy. Please give them wisdom and let them uphold an economic system that is not restrictive.

We also pray for an abundance of energy that will support the growing economies of the world.

We ask You to help people understand the importance of conventional and clean energy sources like coal and nuclear to the developing nations of the world. Lord, let Your wisdom guide the decision makers in academia and governmental institutions.

We pray this in Jesus name,

Amen

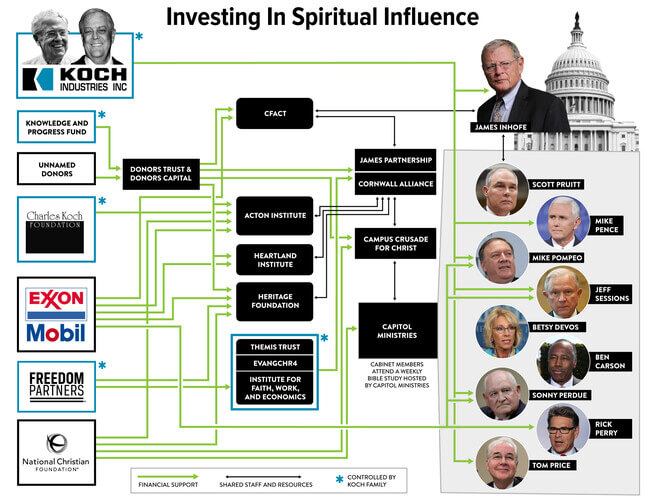

Beisner sent fundraising emails before and after the Trump administration’s announcement that it would withdraw from the Paris climate accord, asking supporters to donate money to the Cornwall Alliance and to implore the administration to pull out of the agreement. Beisner says that the group doesn’t take corporate money and that most contributions come from small donors. But the Cornwall Alliance is in fact a project of a 501(c)(3) nonprofit called the James Partnership, run by Chris Rogers, of CDR Communications, a Virginia-based consulting firm. The James Partnership, financial records show, is embedded in the very same world of shadowy corporate political spending as Heritage and Heartland.

Given that it is a relatively small operation with relatively low overhead, the money that the Cornwall Alliance receives is a vanishingly small fraction of the hundreds of millions spent by the Koch, the Mercer, or the DeVos families. (The Kochs are oil, coal, and gas scions; Robert Mercer is a hedge fund manager who, with his daughter Rebekah, fueled Trump’s rise; Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and her husband Dick are long-time Republican donors).

Their money flows through a multitude of nonprofits, front groups, and donor-advised funds. (A donor-advised fund is a kind of money-laundering service for philanthropists who don’t want anyone to know where their money is going: They make a contribution to the fund, and then tell the fund where to send the money; as a nonprofit, the fund has to disclose all of the grants that it makes, but it does not need to disclose its own donors, nor what direction those donors attached to their money.) Donors Trust, the “dark money ATM” of the conservative movement, contributed $1,001,500 to the James Partnership between 2009 and 2015; in most years, this constituted around half of the Partnership’s total revenue.

“Maybe God will express his judgement through the climate system. One experimental way of trying to test that would be to end abortions and see if climate change ended.”

In 2013, Donors Trust gave only $35,000, but another nonprofit, the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics swooped in with a $100,000 grant; together these accounted for 46.3 percent of the Partnership’s revenue. (Beisner wrote a chapter on why capitalism is less harmful to the environmental than socialism in a forthcoming book to be published by the Institute.) The Institute is controlled by EvangChr4 Trust, a nonprofit dedicated to convincing lawmakers and academics of the Biblical foundations of free-market capitalism; both are run by Paul Brooks, a retired Koch Industries executive. Channelling millions of dollars from the Koch brothers’ Freedom Partners nonprofit, EvangChr4 Trust has also made significant donations to the virulently homophobic and anti-choice Family Research Council—a Coalition on Revival signatory—and CitizenLink (a.k.a. the Family Policy Alliance), the political action arm of Focus on the Family. Both EvangChr4 and the Institute for Faith, Work, & Economics were listed in tax documents as “related organizations” of the Koch brothers’ now-defunct voter database project, Themis Trust; Brooks was also a trustee of Themis. He did not return multiple requests for comment; nor did the Institute.

Donors Trust refers clients to Donors Capital if they are planning to contribute more than one million dollars; the executive director and co-founder of the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty, where Beisner is an adjunct fellow, sits on Donors Capital’s board of directors. Acton’s other co-founder, a Catholic priest, is also part of the Cornwall Alliance. Both Heritage and Acton have received millions of dollars in funding from donor-advised funds administered by the National Christian Foundation, and, as with contributions that come from Donors Trust and Donors Capital, it’s difficult to know whose money is going where when it passes through NCF. As it turns out, the organization that would eventually become the Cornwall Alliance began in 1999, as a project of the Acton Institute, which has received millions from Donors Capital, Donors Trust, NCF, and private foundations controlled by the Koch, DeVos, and Bradley families.

Beisner declined to identify Cornwall or the James Partnership’s more significant donors. When I asked about the contributions from Donors Trust, he said, “You need to deal with the actual evidence rather than just writing it off as bought and paid for by somebody.” Rogers declined to comment.

The “evidence” against climate change, as Beisner and the Cornwall Alliance’s network of scholars interpret it, indicates that whatever fluctuations are happening in the global climate are insignificant—that to whatever extent the climate is changing, the consequences of those changes are not catastrophic. “We think that an infinitely wise God designed, and an infinitely powerful God created, and an infinitely faithful God sustained the Earth and its various subsystems for the benefit of all the living creatures in the Earth,” Beisner told me.

“It could of course always be the case that the all-wise, all-powerful, all-faithful God has so designed the system as to react to abusive action in a manner that expresses God’s judgement on that abuse,” he said. “We abort millions of babies every year. Maybe God will express his judgement of that through the climate system. We have millions of people killed in unjustified wars. Maybe God expresses his judgement of that through the climate system. Or God doesn’t like our pulling coal and oil and natural gas out of the Earth, so he’s going to make the climate system react in a way that would not seem likely on our prior thinking basis.” He added later: “One experimental way of trying to test that would be to end the abortions and see if the climate change ended.”

“A free market economy is the closest approximation in this fallen world to the system of economy revealed in the Bible.”

In 2015, Beisner wrote a position paper on economics and the environment for Acton with Michael Cromartie, a Cornwall advisor and longtime courtier of the secular media. Free markets encourage both competition and stewardship, they argued paradoxically, and are “essential to human welfare.” Therefore, capitalism must have “a moral priority on our thinking about how society ought to be ordered.” The influence of the Coalition on Revival’s Economics “World View” from nearly two decades earlier is clear: “A free market economy is the closest approximation in this fallen world to the system of economy revealed in the Bible.” So concludes nearly four centuries of Calvinist thought, decades of fundamentalist resentment, and several billion dollars in political spending.

Those billions are paying off. Not only have the people who funded Cornwall successfully stopped the government from pursuing policies that might make the lives of people who are living with the consequences of climate change a little bit better, but under the Trump administration their lackeys are actively working to dismantle what little progress has been made. When Drollinger teaches that God’s covenant with Noah means that the consequences of climate change not only will not but in fact cannot be as devastating as scientists believe, he echoes a lengthy essay published by the Cornwall Alliance in 2009 that lays out the same argument. Typical of the organization’s style, it appears to the casual observer like any policy paper drawn up at one of D.C.’s many think tanks and nonprofits; in reality, the document blends quotations from scripture with pseudo-scientific data—citing, for example, the Mercer-funded Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine. During Pruitt’s confirmation hearing, Republican Sen. John Barrasso favorably cited Beisner and the Cornwall Alliance’s support for the Oklahoma attorney general.

“A guy who has given full-throated defenses of coal has told me privately, ‘Coal is dead. We know that. We’re just trying to figure out how to move on.’ Meanwhile he keeps on talking about coal,” Rep. Inglis told me. “Members of Congress are afraid of the people they represent, but they’re terrified of the activists within their own party, because that’s who takes you out in a primary.”

The former congressman recalled visiting Paul Ryan’s district with RepublicEn, his new climate lobby group, to talk about climate change with the House speaker’s constituents. A pair of vocal, anti-environmental activists disrupted the bipartisan event. “At the end of the night, one of my guys said, ‘You realize those are two of the most important activists in Paul Ryan’s district? These two ladies, you sit them in a phone bank, they would wear out multiple cell phone batteries destroying Paul Ryan if they thought he’d gone soft on them.” (When I asked whether he cited that example because Speaker Ryan has privately expressed support for climate action, Rep. Inglis demurred. “Better not go into that,” he said with a laugh.)

“A lot of people tend to go where they find theology that matches their own opinions,” Reverend Hescox told me. “It’s much easier for people, rather than being challenged by the Bible, to find some version of the faith that matches what their pre-existing belief structure is.”

Meyaard-Schaap believes that the green evangelical movement already has sufficient support in Congress for climate action; the issue now is getting the electorate to communicate to their representatives that this is, in fact, what they want. “I continue to believe wholeheartedly that grassroots power is more powerful than small, monied interests. If politicians recognize that there is a bona fide grassroots movement around this issue, and that their seat—regardless of how much money they might be getting from the other side—is in danger, that’s when you get their attention,” he told me. “I think in the next five or ten years, as more and more young evangelicals get plugged into the political process, that grassroots movement is going to grow to the point where politicians who might be getting money from the fossil fuel industry will say, ‘Look, this isn’t gonna cut it. I can’t protect my seat anymore and I have to change tack.’”

Morano dismissed these efforts. “Everything that needs to happen is happening. It’s going to happen naturally,” he said. “If you’re concerned about global warming, sit back and watch the innovation happen. It’s amazing.”

He added: “We just have to have the courage to do nothing.”

This post was produced by the Special Projects Desk of Gizmodo Media Group.