Hurricanes Actually Kill More Americans Than Cars or Wars

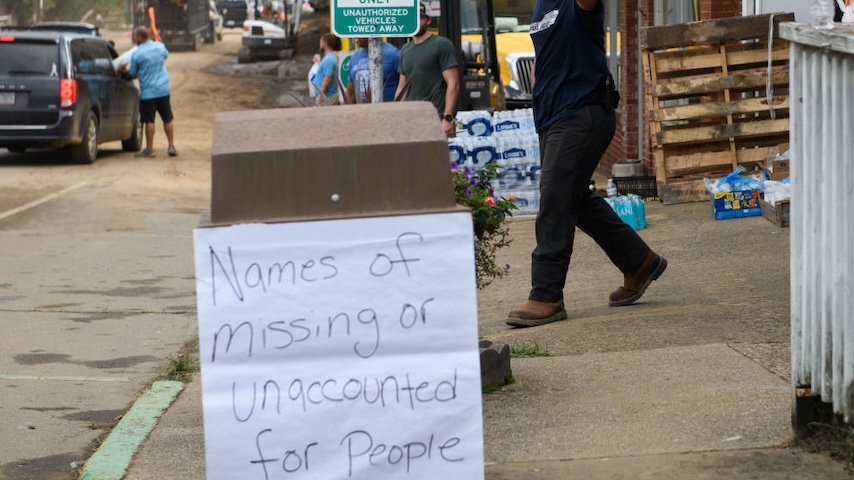

Photo by Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

Hurricane Helene’s official death toll has climbed to 170. This makes it one of the deadliest hurricanes to hit the U.S. in recent memory, and the cleanup and rescue is still ongoing. A new study, though, suggests whatever total gets officially marked in the record books won’t truly reflect its destruction: published in Nature on Wednesday, researchers found that tropical cyclones have extremely long and deadly tails, contributing to thousands of excess deaths in the places they strike over a period of years.

The truly shocking comparisons: between 1930 and 2015, tropical cyclones “contributed to more deaths in [the contiguous United States] (3.6–5.2 million) than all motor vehicle accidents (2.0 million), infectious diseases (1.9 million) or US battle deaths in wars (1.3 million).”

As many as 5.2 million! “We acknowledge that the large difference between the indirect excess mortality burden that we compute and official counts of direct TC [tropical cyclone] deaths is surprising,” wrote study authors Rachel Young and Solomon Hsiang, both of Berkeley, among other places. “Indeed, we initially believed that these findings resulted from calculation errors.”

They concluded, though, that the findings match a growing body of research suggesting disasters like hurricanes do in fact kill many more people than those that are swept away in the immediate flood. Once you start to think it through, there are a lot of mechanisms by which this could happen:

“For example, individuals may use retirement savings to repair damage, reducing future healthcare spending to compensate; family members might move away, removing critical support when something unexpected occurs years later; or public budgets may change to meet the immediate post-TC needs of a community, reducing investments that would otherwise support long-run health.”

Young and Hsiang studied a total of 501 tropical cyclones that hit the U.S. between 1930 and 2015, and estimated changes to state mortality rates in the 20 years that followed those hits. They found that all-cause mortality was raised for 14.3 of those years; in total, the cyclones appear to contribute as many as 88,000 deaths per year.

This is, obviously, well above the official numbers we end up with for individual hurricanes. According to NOAA, the cyclones in this data set killed an average of 24 people (or 22 if you remove the extreme outlier of Hurricane Katrina). But by the new measure, those 24 deaths balloons up to between 7,170 and 11,430 deaths.

These casualties are not evenly distributed. There is the obvious geographic difference, with far more deaths in the states that commonly get hit by these storms like Florida and the Carolinas, but there are also demographic differences. The burden of excess mortality appears highest for infants compared to other age groups, and also highest for Black populations compared with others. Overall, the huge cyclone death counts make up up to an astonishing 5.1 percent of all deaths in the contiguous U.S., but for Black people that proportion skyrockets to 15.6 percent.

“Overall, our findings identify the TC climate as a driver of broad public health outcomes,” the authors wrote. As climate change juices these storms through rapid intensification, excess moisture in the atmosphere, and higher baseline sea level, among other things, this should become a huge focus of further research — the only way to try and lessen the mortality burden of storms as they get worse is to understand where there true danger comes from.

“[M]any affected individuals probably do not realize the extent to which their own health was affected by a TC,” Young and Hsiang wrote. “Identifying the underlying origin of these health outcomes should prompt research and policy to mitigate this human toll.”