Japan Faces Strongest Typhoon in Decades, With Warming’s Fingerprints All Around

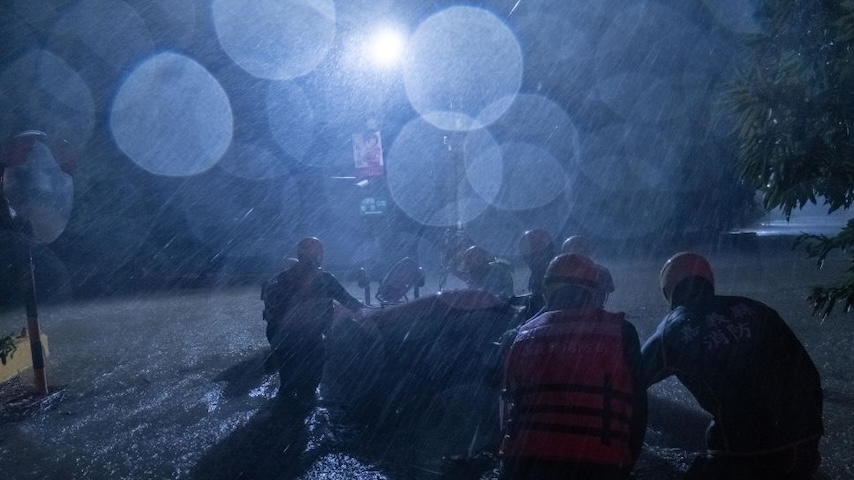

Photo by Lam Yik Fei/Getty Images

For many years, the accepted wisdom was that scientifically speaking we could not blame climate change for the devastation of any individual weather event. Hurricanes have always happened. Lightning can strike a tree and start a wildfire regardless of global average temperatures. The world’s a tough place, floods happen.

That era is long gone. Today, we need only wait the short time from the end of one catastrophe to the start of another to know just how much climate change is making them worse.

To wit: Typhoon Shanshan roared across southern Japan this week, with gusts of wind exceeding 150 miles-per-hour, causing widespread flooding. At least four people have died, and almost 100 are injured; power outages are widespread, flight and train cancelations are rampant, and millions have been told to evacuate. Some parts of the island of Kyushu got more than 15 inches of rain in less than a day. Too much rain.

Though the typhoon has weakened to tropical storm status, it still holds plenty of water, and may well follow a path more or less across the entirety of the Japanese archipelago, flooding as it goes.

On the same day that this catastrophe is unfolding in Japan, World Weather Attribution released their latest analysis, of Typhoon Gaemi, or as it was known in the Philippines, Super Typhoon Carina. That storm caused havoc in the Philippines, killing 48 people and causing widespread damage including a potentially devastating oil spill in Manila Bay, before making landfall in Taiwan where it killed another 10. Like pretty much every storm these days, the scientific analysis made it clear: climate change made it more likely, and worse.

In Taiwan, the presence of the 1.2 degrees C of warming already in place increased the rainfall total by about 14 percent, the study found. The total amount of rain that fell was 60 percent more likely with warming than without; if the world keeps going and passes 2.0 degrees C of warming, this event will be 50 percent more likely still.

The warm seas that fuel tropical cyclones and typhoons are also unprecedented. “Sea surface temperatures as hot as those observed in July 2024 were almost impossible without climate change,” the WWA authors noted. Though they stressed the uncertainty in their modeling, they showed existing warming can increase wind speeds in storms like Gaemi by a substantial margin, and that with 2 degrees warming intensity will increase by a further factor of 10. In the Philippines, they found less convincing trends or associations, though the likelihood of three-day rainfall events has increased by about 12 percent.

Across that whole western north Pacific basin, the researchers showed that category 4-equivalent storms — “major” hurricanes or typhoons with winds between 130 and 156 miles-per-hour — now occur 30 percent more often than without our extra 1.2 degrees. Those storms’ maximum wind speeds are also juiced, by around seven percent.

As usual, a lot of this is about baselines: the sea starts out higher, so floods easier; warmer air can hold more water, so more of it will come down. These attribution studies, which now come fast and furious after many disasters — deadly rain-induced landslides in Kerala, India, hot and dry conditions driving devastating Pantanal wildfires, Mediterranean heat waves that would be literally impossible without warming — are a new norm for science; and the rare example that finds minimal climate change input is very much the outlier at this point. Hotter, wetter, more dangerous — one after another, we now know what’s coming, and why.