Record Coral Bleaching Takes the Climate Change Abstract and Makes It Real

Photo by Andrey Nekrasov/imageBROKER/Shutterstock

In some ways, and for some people, climate change impacts can be easy to ignore or dismiss. Hurricanes hit Florida or New Orleans long before we supercharged them with overheated oceans. Heat waves are dangerous and unpleasant, sure, but summer has always been hot. Sea level rise is incremental and relatively slow, and it’s not always apparent what a millimeter or two per year really looks like.

But when the oceans get so hot for an extended period that the coral all starts to bleach and die, it takes some of the abstraction out of a warming world. It is a severe and meaningful impact, happening right in front of us, with an obvious and undeniable link to warming. The eye-popping colors and delightful biodiversity of a healthy reef giving way to a lifeless moonscape is impossible to misinterpret. It is a warming world’s death knell, laid bare in front of us. And it is getting worse.

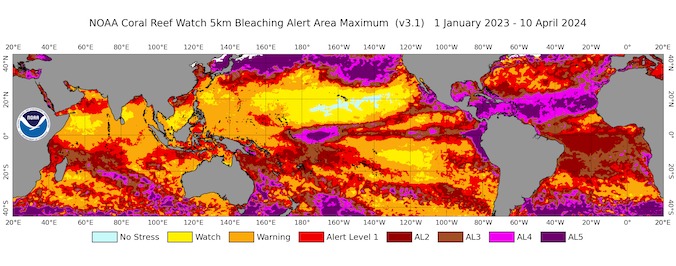

On Monday the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed that the world is now experiencing the fourth global coral bleaching event ever recorded, and the second in just the past decade. This has been going on for about a year, and spans virtually all of the tropics.

There are hotspots in Florida, the Red Sea, the Great Barrier Reef, “large areas of the South Pacific,” off Brazil’s and Mexico’s coasts, and more. Within the next few weeks, it will likely become the most extensive coral bleaching event ever. It’s really bad!

NOAA/Coral Reef Watch

Bleaching happens when the water gets warm enough to stress the coral, which expels the symbiotic algae (literally called Symbiodiniaceae) from their surface. If the water stays warm long enough and the algae can’t make a return, the coral can die. Recovery is possible, but with ocean temperatures now in literally uncharted territory for more than a year such recovery seems unlikely in many places.

Coral reefs support as much as a quarter of all marine species, and offer an astonishing amount of economic benefit to humans: $2.7 trillion per year, according to one estimate. The bleaching that is so readily visible — we can literally see it from the sky — and viscerally understandable is coming for an enormous chunk of that boon.

A 2022 study found that a worst-case climate change scenario would have 99 percent of all reef systems facing “unsuitable conditions” by 2055. Even a best-case version where emissions rapidly diminish isn’t great news: 41 to 64 percent of reefs would be in trouble by the end of the century. The best guess is that the average reef will be in danger by as soon as 2035, and it’s not like we haven’t seen what can happen to them yet: 14% of reefs were already killed by warming between 2009 and 2018 alone.

There is a helplessness to watching this unfold that again feels somehow different from a heat wave, or juiced rainstorm, or extended drought. It simply wouldn’t be happening without the human fecklessness and delay that has characterized our climate response over the past forty years, and its effects will be felt immediately, continuously, for decades.

The only positive spin on this latest event is that El Niño, the Pacific Ocean weather pattern that raises global temperatures, is likely ending soon. There is an 85 percent chance of “ENSO neutral” conditions, between the warming El Niño and the cooling La Niña, developing over the next couple of months; La Niña has a 60 percent chance of showing up later this summer, which could drag the soaring ocean temperatures back into a more survivable range.

But that’s just a potential reprieve, a delay in trial date rather than a full pardon from the charges humans have leveled at these systems. Without true climate progress, it’s only a matter of time.