Study: Maybe Coral Reefs Are Not Entirely Screwed

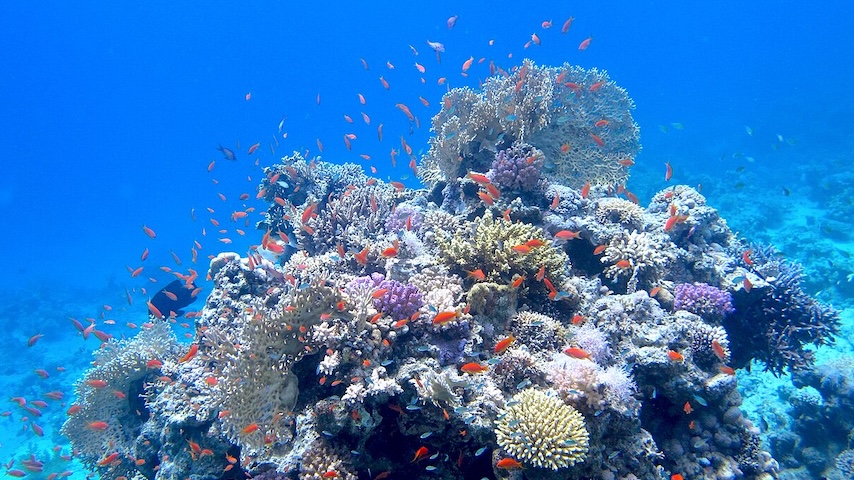

Photo by 74papa/Wikimedia Commons

These days, any news about the world’s coral reefs tends to be bad news. Global bleaching events, the Great Barrier Reef in dire straits — studies have consistently projected and experience as the planet warms has borne out that these biodiversity hot spots are in serious trouble.

So it is worth celebrating, then, when a relative bright result pops up. A study published Tuesday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that some of the gloomy projections may be misplaced; in a physical study researchers found that corals may actually be able to adapt reasonably well to their warming environment — to some extent, at least.

“[O]ur results imply that with effective climate change and local stressor mitigation, reef communities will continue to change, but global collapse of coral reefs may still be avoidable,” wrote authors led by Christopher Jury, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Hawai’i. It certainly says something about the situation that “avoiding global collapse” can be considered a bright spot, but, well, here we are.

Scientists created a “mesocosm” experiment where coral communities were subjected to water temperatures one would expect under a two-degree warming scenario, to ocean acidification of -0.2 pH units, and a combined scenario with both those elements as one might expect in the real world. They found that instead of turning the reefs into “eroding” systems where algae dominated, they stayed as coral-dominated “accreting” systems that continued to build.

That does not mean, though, that nothing changed. “Reef communities that developed in each of warming, acidification, and the future ocean combination of both factors, showed substantial changes in community structure and composition relative to the community that developed under present-day conditions,” they wrote. “Reefs of the future will certainly be different from those of today.”

That means that while the corals continued to grow — coral cover expanded by 21 percent over two years in the combined scenario — the specific species that thrived changed substantially. The authors noted that their more positive results than most other coral research is likely due to three factors, first among them that much of that earlier work examined only three common coral species and others may do better.

Second, other projections assume a near total loss of coral from the reef, causing “carbonate dissolution,” which didn’t happen in this experiment. And finally, this was among the only looks at the combination of warming and acidification, and the authors said the different results with this more real-world scenario just underscores how little we still know about these organisms.

“These reef communities persisted when exposed to chronic warming and acidification for two years, yet they were fundamentally transformed and, in several ways, they were diminished,” they wrote. And since these experiments focused on a two-degree world, the current track we are on — on the order of 2.7 to 3.0 degrees C, under current policies — obviously things could get much worse. “Our results emphasize the critical importance of mitigating both climate change and the intensity of local stressors.”