Study: Ocean Life is Helping Keep Us Cooler Than We Thought

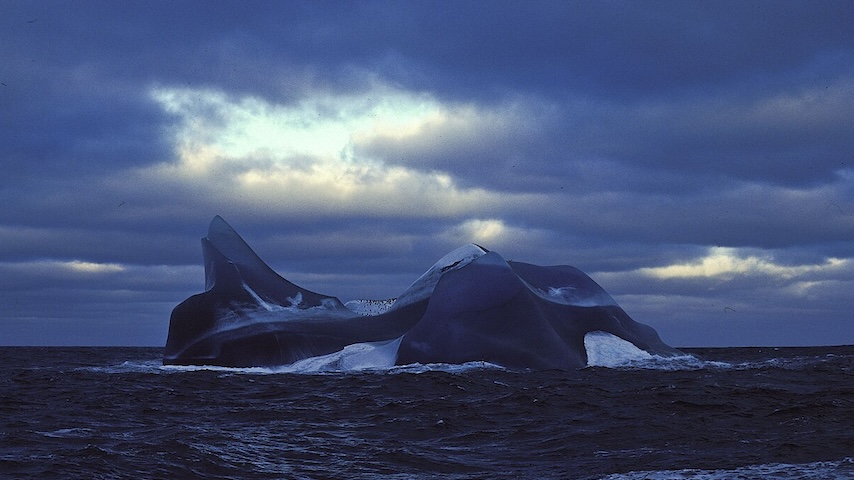

Photo by Hannes Grobe/Wikimedia Commons

The world’s oceans are both a warming scapegoat and climate savior. They have absorbed the vast bulk of the excess heat human activity has unleashed on the planet, and a new study demonstrates some of their tiniest residents are actually helping keep the planet (relatively) cool.

Previously, it was thought that the oceans emitted sulfur in the form of dimethyl sulphide, a residue from plankton that, bizarrely enough, is largely responsible for the distinct smell of shellfish. But there’s another form of sulfur known as methanethiol — the new work, published in Science Advances from a global team of researchers that focused on the Southern Ocean, found that plankton actually emit this gas as well, and in fairly large quantities. This has immediate climate impacts.

“This is the climatic element with the greatest cooling capacity, but also the least understood. We knew methanethiol was coming out of the ocean, but we had no idea about how much and where,” said the University of East Anglia’s Charel Wohl, the study’s lead author, in a press release. “We also did not know it had such an impact on climate.”

The methanethiol rises into the atmosphere and oxidizes, forming sulfate aerosols. Those are the tiny particles that, in contrast to greenhouse gases, have an overall cooling effect, by reflecting sunlight back into space. It’s the stuff that has offset a lot of the warming humans have created, the stuff that was recently reduced somewhat dramatically by a change to international shipping regulations, and the stuff that would most likely be used if the world or some rogue actor ever decides to start a solar geoengineering program.

The world’s plankton is conducting its own geoengineering work, apparently. The researchers found that the methanethiol they produce actually bump up the total marine sulfur emissions by 25 percent.

The main result here is to close some knowledge gaps. “Climate models have greatly overestimated the solar radiation actually reaching the Southern Ocean, largely because they are not capable of correctly simulating clouds,” Wohl said. “Knowing the emissions of this compound will help us to more accurately represent clouds over the Southern Ocean and calculate more realistically their cooling effect.”

Basically, the climate models we use to project warming and better understand the overall climate system weren’t really accounting for the marine methanethiol emissions; now they can. We already knew the oceans were valiantly trying to save our asses; now we can give them closer to proper credit.