The Climate Charts Are Still Not Okay

Photo by Ayla Meinberg/Unsplash

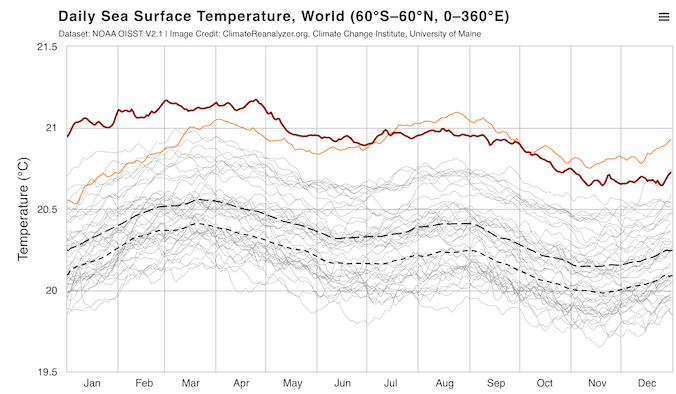

The first piece I wrote when I started at Splinter back in March was about a chart. A chart that I looked at every day, that had lodged itself in prominent corners of my brain in such a way as to render it constantly visible, omnipresent. At the time, it depicted a global average sea surface temperature, poles excluded, that so far exceeded that of previous years that it seemed like a mistake. To me, it took on an air of personification, climate change itself taken demonic form.

Not unsurprisingly, the line for 2024 did begin to find its way back to, if not the pack of years dating to 1981 when these records began, then at least to the previous leader. In mid-summer, it finally touched its nearest competitor — 2023, of course — and then dipped below it, where it has largely remained since. Again, this makes sense: the El Niño of the previous year had faded, taking its warming influence with it and landing us in a “La Niña Watch” phase, according to NOAA. Sprinkle in at least some degree of natural variation and sure, it makes sense that the world’s oceans wouldn’t just set a new record every day forever.

But that’s what I wrote back in March — “It is normal for the theoretically abnormal to occur. It would be weird and unexpected now if the records stopped falling.” Once this particular chart stopped showing record warmth at each successive viewing, I confess I stopped checking it so often — a few times a week, maybe only once by the time October or November rolled around. Other climate issues took root in those prominent brain folds, shouldering out the chart in favor of rapidly intensifying hurricanes, flooded continents, a United Nations climate conference that felt like a step backward off a cliff.

If it wasn’t that record, that particular chart, that specific marker of a warming planet, it was still certainly something else. It was more rainfall in a day than a given spot had ever experienced, or a glacier receding faster than ever recorded. Or, of course, that baseline marker of climate change, the planet’s overall air temperature: 2024 will go down as the warmest year in the century-plus of record-keeping, meaning it beats out 2023 by a substantial margin, which itself was likely the warmest year in at least 125,000 years. One chart might sink back toward a resting state, the world briefly correcting an anomaly never seen before, but some other chart will fill that void.

And the oceans are still, of course, hot. The current anomaly, according to the chart, is almost half a degree Celsius above the 1991 to 2020 average; for this moment of the year, that’s still second only to 2023. Even the victories feel like defeats in a world this warm.