The Desperate Battle For Unions' Blessing in 2020

Like thirsty desert travelers converging on a shimmering oasis, Democratic presidential candidates flocked to the Iowa Federation of Labor convention last week. An endless parade of hopefuls, comedic in length and wearying in content, came before the union delegates in a hotel ballroom, each with a promise in one hand and a begging cup in the other, paying homage to organized labor. All of the Democrats lustily eyeing the Oval Office know that union support is a necessary ingredient in their success. They will not reach the promised land without it. And so they come, partaking in the political beauty pageant, looking to win affection.

For America’s beaten-down unions, this is the opportunity of a generation. Strike the right deal, and they might see the turnaround they’ve long desired. Strike the wrong deal, and, well…we all saw what happened in 2016.

From the perspective of a presidential candidate, union support is the sweetest support you can get. Unlike wayward regular voters, who lose interest and are constantly seduced by competing pastimes, unions can still command great blocs of support; they can be counted on for money, and for an army of door-knockers and sign-wavers and get-out-the-vote rally-goers; they are one of the closest things that our atomized society has to a true political army. The decades-long decline of unions, down to barely ten percent of the workforce now—a decline carefully engineered by business interests and their Republican allies—has harmed the Democratic Party by depriving it of that army and its resources. But there are still nearly 15 million union members in America, and the slice of those who are well-organized and engaged is still large enough to give an enviable boost to any candidate. And so we are, at this moment, in the most heated phase of courtship between labor and politicians. The Democrat who wins this beauty pageant will be virtually guaranteed the honor of facing off against Donald Trump, whose administration has overseen a structural assault on unions that has been far too successful for comfort.

This is the time for organized labor to make its demands.

The Prairie Meadows Hotel and Casino is the only big unionized convention-capable operation in the Des Moines metro area, and so it is here that the Iowa Federation of Labor gathered, in a ballroom with white ceilings and grayscale carpeting just downstairs from a mass of slot machines looking out at a horse racing track, for the biggest audition of Democratic candidates before the Iowa caucus in early February. Fourteen—fourteen!—candidates showed up in person. (Jay Inslee, who was also scheduled to appear, dropped out of the race, and Bill de Blasio spoke via video from New York, though an unfortunate technical glitch sped up the audio and made him sound like Donald Duck.) The numbers speak for themselves. Every single major and minor presidential candidate does not trek to an event in Iowa unless it represents a constituency that is considered absolutely mandatory for victory.

In the days surrounding this event, both sides took advantage of the attention: Unions, to make their demands, and candidates, to release plans dealing with union issues in hopes of wooing support. The two million-member SEIU, America’s single most politically powerful union, announced a “Unions For All” plan that amounts to a road map of what they expect 2020 candidates to get behind. It’s markedly more ambitious than the purely technical sorts of legal fixes that unions have focused on in the past. Most notably, the SEIU wants sectoral bargaining, which would allow union contracts to be negotiated for entire industries, rather than just in individual workplaces. This model, which is prevalent in some European countries that are among the world’s most union-friendly, would allow organized labor to achieve a scale in the U.S. economy that it probably never will if it continues to be forced to organize shop-by-shop. In addition to that, the union wants a variety of stronger federal labor laws, a commitment to make the jobs in big government programs like Medicare For All and the Green New Deal union-centric, and for the federal government to ensure that all of its contractors offer strong wages and protections for workers who want to unionize. In a speech, SEIU president Mary Kay Henry said that her “mission” for the rest of Democratic primaries and through the general election will be to get Democratic candidates to commit to these goals: “To get these candidates to understand us. To get these candidates to stand with us. To get these candidates to demand with us: Unions for all.”

That’s about as explicit a mandate as you will find. Unions are in the business of building and exercising leverage, and their leverage with Democratic candidates is at its maximum point now. And candidates—the smart ones, at least—are reciprocating. Bernie Sanders vaulted himself to the front of the line by releasing a “Workplace Democracy Plan” that is, in essence, a laundry list of every pro-union policy that a room full of union strategists might be able to come up with in a brainstorming session. It includes not just sectoral bargaining (which would, in itself, be the biggest pro-worker policy in decades), but also things that unions have long salivated over, like card check (which would make a workplace automatically unionized when a majority of employees signed union cards, getting rid of the long and challenging process that now exists); a provision to force mediation over union contracts after four months of bargaining (meaning employers could not stall for years, as many now do); protection of endangered union pension plans; re-instituting rights for public employee unions that have been stripped away by Republican governors and courts; and the repeal of the worst parts of the hated Taft-Hartley Act, like “right to work” laws that have nearly eradicated unions in half the states in the country. It also, not coincidentally, includes the connection between federal contracts and high labor standards that the SEIU asked for. There’s much more, too. If you can imagine a pro-union law, it is probably in there. Beto O’Rourke also released a fairly strong labor rights plan to coincide with the convention. And Bill de Blasio grabbed a bit of attention last month with his “Workers’ Bill of Rights” proposal. It will be hard for any candidate to exceed Bernie’s plan, because he put damn near everything in his, but you can expect that a number of other Democrats will be pushing their own policies towards his. The bar has been set. The bar is high.

[Minutes after this story was published, Bernie was endorsed by the United Electrical Workers union.]

Today, unions seem to have accepted that they are in a war. They know that their votes may well be the difference in the presidential election. And if they win, they want the changes to be big.

It’s necessary to keep this all in perspective. That old Taft-Hartley Act, the U.S. government’s harshest legal assault on unions, passed in 1947. For 70 years, Democratic presidents have flirted with rolling back some or all of it. And yet, they all failed. Here we are. The world of labor policy does not lack for plans. Every year, there is a blizzard of white papers about “The Future of Work” and “Reforming Labor for the 21st Century” and things like that. You could build houses of these papers. They all say more or less the same things—the sort of things that are contained in Bernie Sanders’ Workplace Democracy Act. And despite the booming employment in the Labor Policy White Paper Generating sector, union density tends to keep declining every year, and wages for most workers have stagnated for decades, and right-wing forces have successfully captured the White House and the courts and most statehouses and Congress. Plans are cheap. What unions need is power. The power to make those plans a reality.

At the Iowa Labor Federation convention, the candidates were giving their pitch that they could not only be the best friend that unions have ever had in the White House, but also that they are passionate and savvy and powerful enough to make all of these lovely promises come true in the real world, where filibusters and Mitch McConnell and gerrymandering and the Koch brothers (or at least one of them) exist. The hotel ballroom was—as all union conventions are—hung with union banners and full of round tables at which were seated a lot of middle-aged men with mustaches wearing a lot of t-shirts emblazoned with the names of their union locals. A tinny version of “Solidarity Forever” played over the speakers to open the meeting on Wednesday. The distance that America’s political center has drifted to the right can be measured by the fact that Ken Sagar, the sober-looking and mild-mannered president of the Iowa AFL-CIO, gave a speech that would be classified as “left-wing” in the political media, but really amounted to a man with a typical Midwesterner’s dose of basic decency surveying the wreckage of the post-Reagan era inequality crisis. “If [working people] truly are the majority, then how is it we ever lose elections? Because they turn to an age-old practice called divide and conquer,” Sagar said. “Our country is so polarized right now that it scares the shit out of me.”

After a rather grandiose introduction, national AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka joined the meeting via video. “Being a Democrat is not a qualification for our endorsement, and being a Republican is not a disqualifier,” Trumka said, in a noble effort to maintain leverage that is meaningless in the context of the 2020 presidential election. If that endorsement is earned, he said, “We will move heaven and earth to elect you.” Judging by the 15 candidate names listed on the day’s schedule, that is what was expected.

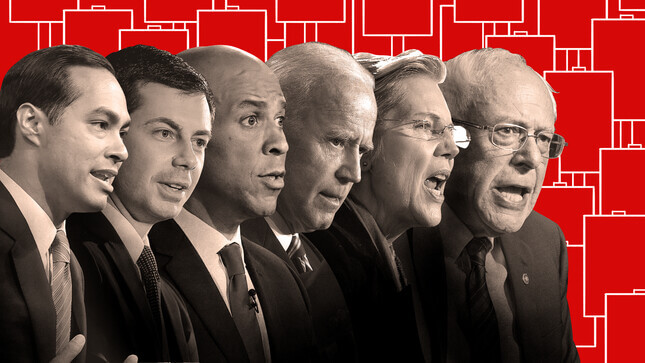

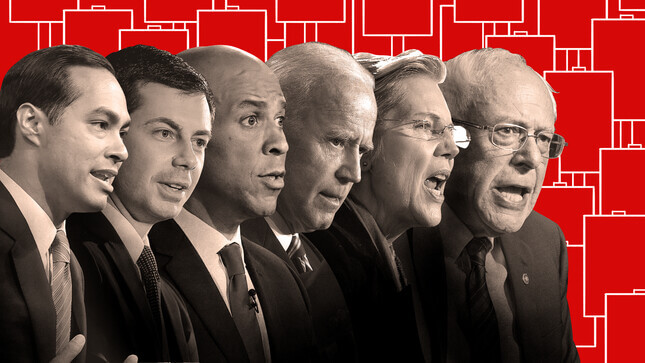

First came John Delaney—who, though he may have the smallest rational chance of being the AFL-CIO’s choice for president, still earned some whistles as he walked out, which I attribute completely to the fact that he was the first candidate of the day. (As the hours rolled by, the crowd’s enthusiasm would become harder to earn). Delaney talked mostly about his infrastructure plan. The benefit to unions was implied. His dad was in the IBEW. Then came Elizabeth Warren. She’s walked picket lines and called CEOs during strikes! Her own campaign staff is unionized! “Unions built America’s middle class, and unions will rebuild America’s middle class,” she declared, making sure to note that “I don’t just say it when I show up in this room—I say it every time.”

Cory Booker’s grandfather was a UAW member. He supports the dignity of labor. Bernie Sanders hit the high points of his newly announced plan, bragged about his 100 percent rating from the AFL-CIO, called Donald Trump a “pathological liar,” and earned a standing ovation. Bill de Blasio suffered his high-pitched voice audio debacle as he called in to explain he that he puts “working people first.” (They later replayed his entire speech with the audio corrected, though de Blasio’s squeaky appearance was already a nationwide punchline by then.) Joe Biden meandered through a vague set of assurances that, folks, I’m not kidding, I been saying it for 30 years, I’m not joking—we need unions. He concluded with the desperate plea, “God love ya. I need ya. You’ll never have a better friend in the White House!”

Julian Castro—dapper, wonky, reasonable, and calm—called for cerebral policies like better National Labor Relations Board appointees and indexing the minimum wage to inflation. He’ll make a great mid-level cabinet secretary in the administration of a president who is a more exciting speaker. Pete Buttigieg—also dapper, wonky, reasonable, and calm, though more “McKinsey alum” than “I was the first in my family to go to college”—advocated focusing our economic measurement on broad-based income growth, rather than on GDP. Not a bad idea but not a huge applause line.

Steve Bullock bragged about being a union-side lawyer in an earlier career. Michael Bennet called for tax credits in his sleepy Muppet voice. Amy Klobuchar’s grandpa was a Teamster. She complimented her own jokes. Beto O’Rourke mostly talked about gun control, but managed to shout out the IBEW in El Paso. Even Joe Sestak, the former admiral who is almost physically incapable of speaking about anything other than aircraft carriers, forced himself to say something about workplace safety. “If you work in a popcorn factory, it’s like inhaling acid,” he said, mystifyingly. Good to know.

By far the most energetic—or perhaps desperate—candidate of the day was Ohio Congressman Tim Ryan, whose long-shot appeal was leavened by the furious intensity of his speech, which grew in volume over the course of ten minutes until he seemed to be begging for union support in the way a hostage might beg his captors for his life.

“I will pull every lever of power for you. I will be your president. You can take that to the bank!” he yelled. “Give me a chance, give me an opportunity, I will win Ohio, I will win Pennsylvania!” It was the sort of complete debasement at the feet of organized labor that we should want in the White House. On the other hand, the pleading was a little disturbing.

At any rate, one of these people will be selected to carry the union flag. The union world can afford to be picky. The president is unpopular, the left is angry, and they have a huge buffet of candidates to choose from. There is no doubt that the Democrat will earn labor’s endorsement in the general election. The more immediate question is whether big unions will endorse in the Democratic primary. With the exception of the firefighters union, which endorsed Joe Biden as soon as he declared for the race, organized labor has held its cards close. For good reason—as the response to the SEIU’s ultimatum has already shown, there are significant concessions to be extracted now, by holding out the possibility of an endorsement down the road.

One school of thought in the union world is that they should not endorse in the primary at all, because it has the potential to divide the party and spark a rerun of the vicious Bernie vs. Hillary wars of 2016. Indeed, when you speak to America’s most politically active unions, it becomes clear that the bitter memory of the internal dissent and anger of four years ago is still fresh on their minds. The AFL-CIO endorsed Hillary Clinton a full month before the Democratic convention last time—when she was a sure thing in the minds of the Democratic establishment, but while Bernie Sanders (an objectively better candidate on labor issues) was still in the race, pissing off millions of leftists rather than rallying union members around Hillary’s campaign. There is a very good chance that the AFL-CIO itself will not endorse a candidate this time around until the race is completely sealed up. (AFL-CIO officials did not return requests for comment.) But that is not necessarily true for individual unions themselves, who, with so much potential influence on the line, will be tempted to try to achieve the delicate combination of union democracy and hardball politics.

All of the major unions that I spoke to said that an endorsement from them in the primaries is possible; but they also went out of their way to emphasize that such an endorsement would be based on the will and assent of the members. Randi Weingarten, the head of the 1.7 million-member American Federation of Teachers, told me that she’s focused on transparency and credibility in this election cycle, to avoid the rancor surrounding her union’s endorsement of Clinton last time. Though she defended that endorsement as being fully in line with the votes of members, she admitted that “the fact that people felt it was rigged was a problem.” This time, the union has an extensive, formalized process in place, including candidate town halls across the country, to decide on an endorsement. Weingarten said that the AFT would not endorse before early spring, at the earliest. Even then, the bar is high. When I asked her what it would take for her union to jump in with a primary endorsement, she mused that it might happen if it was necessary to block a truly bad candidate: “Say Howard Schultz got back in the race, and he was winning…”

Likewise, AFSCME, the 1.4 million-member public employees union that could be one of the most directly damaged by the recent anti-union Janus Supreme Court ruling, feels comfortable holding out an endorsement as a possibility to see how pro-union these Democratic contenders can get. “AFSCME will consider endorsing, but we have no timeline and we will do so only if a consensus emerges as a result of our deliberative and democratic endorsement process that one candidate stands head and shoulders above the others in terms of who is going to fight for working people,” said AFSCME president Lee Saunders. “I would argue that this field of candidates is the most pro-union and pro-working families in decades, and so there’s no reason for us to rush into a decision. 2020 is very different and so is our approach this time around.”

To win outright endorsements from any of the most powerful unions, candidates will have to work. The three million-member National Education Association, America’s biggest union, says it is in the “early stages” of its endorsement process—for which they require all candidates to sit for a recorded interview with the union’s president, which members can view online. For months already, the SEIU has been arranging meetings between candidates and members of their various locals across the country; they (like other unions) had candidates make a pilgrimage to a forum to address them; and multiple candidates have walked picket lines with them, most prominently for fast food workers affiliated with the Fight for $15. Mary Kay Henry, the SEIU’s president, has said, “we will be looking for their robust plan on how to unrig our economy so that black, white and brown working families – not just corporations and billionaires – can thrive. Their plans must include ensuring everyone has the chance to join a union, no matter where they work.”

The inclusion of that sort of ultimatum, which would amount to a radical (and necessary) revision of our nation’s labor laws, testifies to the fact that the one-upmanship that will accompany this election cycle’s large field will mean a bounty for labor. If the Democrats win. The grim memory of 2016, when Hillary Clinton won the union vote by a paltry 51-43 margin, the closest in decades, still looms large. The knee-jerk reaction to that poor showing from much of the union establishment was that unions needed to re-focus on the needs of the mythical “white, working class voters” who, in the stunned post-election narrative, were held up as the key to Trump’s victory. But survey where we stand now, and it is clear that that narrative has fallen away. The awful realities of Trump’s policies—systematic union-busting by judges and regulatory agencies, xenophobic anti-immigrant fervor, shameless tax cuts for the rich—have pushed labor leaders towards more radical conclusions. The appetite for compromise or working with the White House was quickly stomped out. Today, unions seem to have accepted that they are in a war. They know that their votes may well be the difference in the presidential election. And if they win, they want the changes to be big.

The Culinary Workers Union in Las Vegas represents the vanguard of American labor unions: united, omnipresent, progressive, and widely acknowledged as one of the most powerful political forces in the state. They are legitimately capable of delivering Nevada to the Democrats. This year, their spokesperson Bethany Khan says, “Our union is committed to defeat Trump on Election Day.”

They want immigration reform; they want healthcare; they want to see presidential candidates taking their side in labor disputes, loudly and publicly. But they have not forgotten that politics is not simply a quid pro quo for shiny things. The biggest thing to be won in 2020 is not any government handout offered as a straightforward trade for union votes—it is the definitive end of the U.S. government’s legal war on organized labor, which has been continuing with only brief pauses for the past 70 years.

“We are a union that does some political work,” Khan notes, “not a political organization that does some union work.”