There Is No Disagreeing With Heat This Hot

Image via NOAA/NASA

There wasn’t much drama in NASA’s and NOAA’s announcement this week that, based on their respective datasets, 2024 was the warmest year on record. Though NOAA’s prediction algorithms began 2024 with only a limited chance of the year breaking 2023’s absurd heat record, by the time late summer rolled around the monthly reports were showing a 95 percent-plus chance of it happening. By the fall, the chance exceeded 99 percent.

“This is not really new news at this stage,” said Russell Vose, an expert with NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, during a call with reporters on Friday. “It’s more of a confirmation for what we all suspected was going to happen.”

Vose’s counterpart at NASA, director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, agreed during the call: “2024 was in fact the warmest year on record, and the gap between 2023 and 2024 was was significantly outside of our estimated uncertainties,” he said. “There’s really no question about that.”

The numbers: NOAA says 2024 was 1.29 degrees Celsius above a baseline average from 1901 to 2000, and 0.1 degrees C warmer than 2023. NASA found it was 1.28 degrees C above a 1951 to 1980 baseline, and 0.11 degrees warmer than the previous year. Both basically agreed with the generally misleading headlines proliferating around the world today, that 2024 was likely the first calendar year that the global average temperature exceeded 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial temperatures; this does not, however, mean the Paris Agreement target is dead. For that, we’ll need a decade or two of temperatures above the 1.5 degree mark. Still, hot is hot.

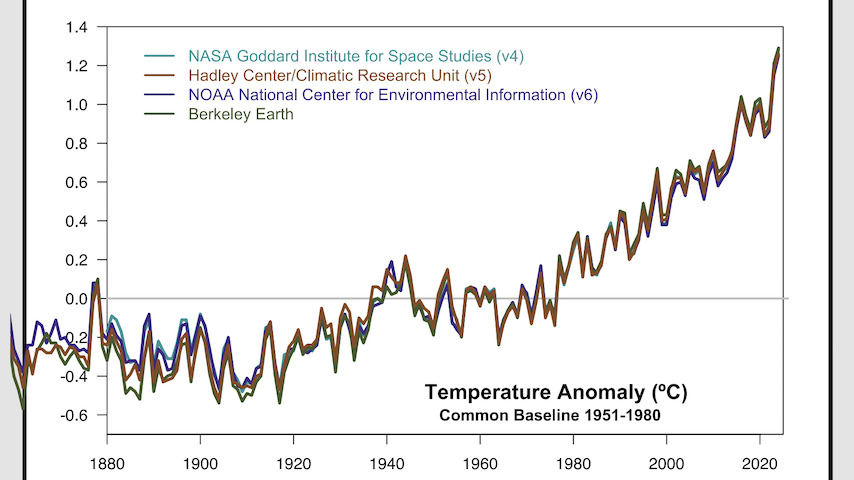

The final slide Vose and Schmidt showed to press during their call on Friday is a striking one: seen above, it shows four different global temperature data sets, the two U.S. government agencies joined by the U.K.’s Hadley Center and the independent research group Berkeley Earth. The lines to the right of the chart might as well be one, a lockstep climb up a mountain of warming.

This is notable only in that the disagreement between data sets, such as it was, or even just the relative paucity of those sets, used to provide some degree of cover for deniers or delayers out there. Berkeley Earth was in fact founded by a self-proclaimed “climate change skeptic” who thought there were such significant holes or errors in existing temperature records that it needed an overhaul. The skeptic changed his tune years ago, in 2012, but still — Berkeley Earth’s 2024 analysis found the year was the warmest since 1850 when records begin, “exceeding the previous record just set in 2023 by a clear and definitive margin.”

They could have added more groups to the chart. The Japan Meteorological Agency, the World Meteorological Organization, it doesn’t matter — all agree we’re in unprecedented territory here. During the press call, Vose said that even the University of Alabama in Huntsville’s satellite temperature data set, long used by grifters and bad-faith politicians as some sort of counter to the entire concept of global warming, showed a 2024 record beyond expectations, a remarkable 0.3 degrees C above the previous mark.

The reasons for the last two years’ global temperature spike remain the subject of intense scientific scrutiny. The influence of El Niño, the drop in cooling pollution from an international shipping regulatory change, feedback loops from diminishing sea ice, other factors entirely — it is not 100 percent clear, yet, whether these are a blip in the otherwise more linear upward trend, or yet another layer of “new normal” layered upon the existing warming trend. But the disagreement at this point on the global average temperature itself is tiny, on the order of fractions of fractions of a degree from one source to another.

During the call on Friday, Schmidt pointed out that as you travel back in time along that chart, you start to see more divergence in the lines. This is because of gaps in the data in that earlier period, back into the early 20th and the late 19th centuries — the world was not so covered by sensors in 1900, nor the technology so good as to be completely trustworthy. The result, then, is that the various data sets will differ today only in how they see our current sweaty condition departing from those baselines — agreeing on a 1.5-degree anomaly requires that the various sources agree on where we started, and the farther back we go the harder that gets.

“You cannot expect a clean answer for when we will have passed a level like 1.5 or 2 [degrees] or anything,” Schmidt said. Such a moment is, of course, largely academic — it is hot, everyone who isn’t selling something now agrees, and getting hotter, and the arbitrary round-number thresholds set forth in global agreements will fall when they fall. “These are going to be things that are clearer in retrospect.”