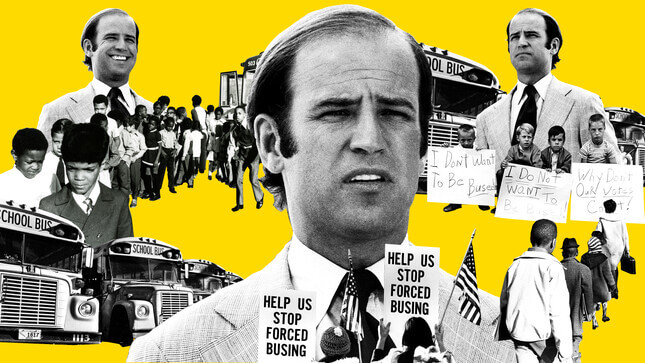

When Joe Biden Chose the Wrong Side of History

In November 1976, at the height of Delaware’s decades-long fight over desegregation in schools, Sen. Joe Biden spoke to a class of about 120 schoolchildren from Newark, DE, who were visiting Capitol Hill. As the Wilmington Evening Journal reported the following day, Biden told the all-white crowd of fifth-graders, chaperones, and onlookers: “Black kids don’t want to go to your school any more than you want to go to their school.”

Weirdly, Biden’s comment was part of his attempt to encourage the kids to accept the idea of having black classmates after a federal court ordered the desegregation of public schools in Wilmington and New Castle County, 22 years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling. (“You shouldn’t hate black kids,” he told the students. “They had nothing to do with it.”) But Biden was no crusader for desegregation busing—the system in which children were bussed to schools, sometimes far away from their homes, in an attempt to integrate schools—even though it was the most potent tool that the courts and bureaucracy had to end school desegregation, and was fervently supported by civil rights groups. “I don’t think it’s a very smart idea,” Biden responded to a question about desegregation busing on that November day, even as he encouraged the students to “act like good kids” if their schools were integrated.

Judicious positions, though, don’t get you votes. Biden quickly started to move rightward, transforming himself into an anti-busing leader in the Senate.

Biden wasn’t just a bit player in the fight over desegregation busing. During the second half of his first term, which came at a time when Delaware was much more reliably Republican than it is today, Biden became a national leader in the anti-busing crusade, making frequent common cause with Southern segregationists. The irony was not lost on Biden, who was elected as a liberal reformer in Delaware in 1972, and who spent his first two years in office as a relative supporter of busing before making a sharp right turn.

As Congressional Quarterly wrote in October 1975 of a Senate debate that September on busing, Biden at one point found himself huddled in a conversation with some of the 20th century’s most infamous racists: Jesse Helms of North Carolina, Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, and James Allen of Alabama. “For a brief moment, Biden said,” according to the paper, “he was convinced he was in the wrong meeting.”

Biden’s opposition to busing, like his other controversial stances that have come in conflict with civil rights groups (authoring the infamous 1990s crime bill and the Anita Hill hearings chief among them) has come up several times later in his political career, most notably in a New York Times piece published during his run for vice president and a 2015 Politico story published while Biden weighed a run against in Hillary Clinton. More recently, both the Washington Post and the conservative Washington Examiner have resurfaced interviews Biden gave during the height of the busing controversy. In the latter, a 1975 interview with NPR, Biden argued that desegregation was “a rejection of the entire black awareness concept.” And on Thursday, CNN published never-before-seen letters from Biden sent to infamous segregationist Mississippi Sen. James Eastland, courting and thanking him for his support on Biden’s anti-busing bills.

As damning as those pieces were, firsthand accounts from the 1970s are, in some cases, even worse. A review of local Delaware news accounts from the time, as well as the Congressional Record, shows the depths of how troubling Biden’s stance on busing was, as well as how cynically he appeared to be responding to political pressure. It also shows that, in turning so staunchly against busing, Biden was unequivocally siding with segregationists in the interest of political expediency on one of the most important civil rights questions of the era.

And given this disturbing chapter in his past, it’s worth pondering how a President Biden would respond to similarly divisive civil rights challenges now. Would he side with vulnerable communities—or, as he did during the busing controversy, would he pander to white racism?

You can draw a direct line from Biden’s hardline stance on busing to the fact that he spent 44 uninterrupted years in federal elected office. Without it, he very well could have been defeated after one term.

Delaware had been at the heart of the fight to integrate schools; when the Supreme Court heard Brown in 1954, it combined five similar civil rights cases. One was Gebhart v. Belton, which was brought by a black family in the Wilmington suburb of Claymont. But even after the Brown decision, Delaware continued to have trouble actually desegregating its schools, largely due to the fact that neighborhoods themselves remained segregated.

According to a 1975 New York Times story about a lawsuit against the state board of education, schools in Wilmington, the state’s biggest city, were 83.6 percent black, while “all but one of the 12 districts in New Castle County, which surrounds [Wilmington], are at least 93.2 percent white.”

Clearly, school segregation and busing were potent political issues. And in his first campaign for Senate, in 1972, Biden’s stance on busing was all over the place, ranging from dismissive to outright hostile.

In an early report on his then-nascent Senate candidacy against incumbent Sen. Cale Boggs in March 1972, the News Journal quoted Biden as calling busing a “phony issue which allows the white liberals to sit in suburbia, confident that they are not going to have to live next to a black.” In a September press conference during the campaign, Biden responded to a Delaware Human Relations Commission report recommending redistricting city schools to desegregate them by saying that “racial balance” in schools “in and of itself means nothing.” In his 2008 autobiography, he called it a “small side issue” during his first campaign.

During an election debate in September 1972, Biden said he would oppose a constitutional amendment against using busing to achieve racial balance in schools, but with a caveat: he supported busing only to fix segregation enforced by law. “The Supreme Court never said you can bus for racial balance or to avoid de facto segregation,” Biden said.

Biden’s actions in the Senate early in his first term, however, mostly failed to match his tough talk on the campaign trail. According to the Wilmington Morning News’ contemporaneous accounting of busing votes by both Biden and Delaware’s Republican Sen. Bill Roth, Biden cast 16 pro-busing votes in his first two years (1973 and 1974) to just four anti-busing votes. That ratio would soon be turned upside down.

“I have become convinced that busing is a bankrupt concept that, in fact, does not bear any of the fruit for which it was designed,” Biden said.

In June 1974, a month after voting against an amendment that would have stripped the federal courts of their ability to order busing, Biden accepted an invitation to speak about busing before a local civic association. A “neighborhood school association coordinator” told the Morning News: “We’re going to hound Biden for the next 4 years if he doesn’t vote our position.”

When Biden faced the crowd of 250 people on July 9, he faced a barrage of pissed off suburbanites. According to a Morning News report the following day, Biden explained that he had voted against the amendment because of a provision in the measure that would “permit the reopening of any desegregation suit.” Biden also reiterated that he’d support busing to end segregation by law, even going as far as to say: “I’d support the use of helicopters.” The crowd, as you can imagine, was not happy.

Three days after the meeting, the News Journal praised Biden in an editorial. “It took guts for Sen. Biden to face that hostile crowd,” the paper wrote. “It took even more courage for him to have voted the way he did, knowing full well that sentiment in much of Delaware runs against his judicious position.”

Judicious positions, though, don’t get you votes. Biden quickly started to move rightward, transforming himself into an anti-busing leader in the Senate.

That December, the late News Journal columnist Norm Lockman—the first black reporter to be hired full-time by the paper, as his obituary noted—summed up the civil rights position, using the example of Boston:

To push racial balance as an educational remedy in a school system that has suffered an overall collapse, as the Boston public system has, is irrational. But Boston doesn’t totally invalidate the theory of busing to achieve quality education for deprived kids as much as many people would like to think that it does. For that reason, the power to use busing as a tool must not be destroyed.

In particular, Lockman took issue with a Biden speech in late 1974, which Lockman said “has to be considered an advance notification of a switch to an unqualified anti-busing position”:

It would seem unfair, to me, to take away a means which some school system might have to rely upon as the only way it could use in good faith to comply with federal school desegregation laws…a conceivable extension of Biden’s current anti-busing lean would seem to lead to a need to change basic school desegregation law. I’m sure that a distaste for bad busing plans is not worth that.

Lockman’s prediction proved to be prescient. By 1975, Biden was a full-fledged anti-busing crusader on the issue. According to the News Journal, 1975 through 1977 saw him flip almost completely on busing, casting 19 anti-busing votes and just one pro-busing vote.

He also began getting friendly with some of the most virulent racists in the Senate. During one floor debate over busing in September 1975, Biden stood up and said he “supported, at least in principle,” an amendment offered by Jesse Helms. “The Senator from North Carolina welcomes the Senator from Delaware to the ranks of the enlightened,” Helms said to laughter. (Later, Helms added that the comment was “in friendly jest, but I do welcome [Biden] to the ranks of those of us who have been fighting this insanity of forced busing.”) Added Florida Sen. Lawton Chiles, another opponent of busing who “commended” both Helms and Biden: “I am delighted to see the enlightenment that is beginning to go on.”

“I have become convinced that busing is a bankrupt concept that, in fact, does not bear any of the fruit for which it was designed,” Biden said. Later in the debate, he compared desegregation busing to Vietnam:

Let us not make busing in relation to the social issues of the day what Vietnam was to our foreign policy. Vietnam we found out did not work in 1965, and some tenaciously held onto it as if it were some way out of foreign policy, and we started to talk about our national image and what it would do to us instead of doing what the farmer senior Senator from Vermont, Senator [George] Aiken, said, namely declare that we won the war and leave. I think we should do the same thing with regard to the social issue and declare busing does not work, leave it, and get on to the issue of deciding whether or not we are really going to provide a better educational opportunity for blacks and minority groups in this country.

Biden rewrote Helms’ amendment to make it just as effective in preventing the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now HHS) from using federal funds to integrate schools but more palatable to anti-busing liberals and moderates from the North. His main opponent in this debate was Republican Sen. Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first African-American to serve in the Senate after Reconstruction.

Biden’s amendment passed 50–43. (He would later write other successful anti-busing amendments as well.) As Jason Sokol wrote for Politico in 2015, Brooke described Biden’s successful amendment as “the greatest symbolic defeat for civil rights since 1964,” and that it was “just a matter of time before we wipe out the civil rights progress of the last decade.”

He embraced his newfound zeal for the issue, viewing himself as something of a pioneer. “I think I’ve made it possible for liberals to come out of the closet,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer in October 1975. “If it isn’t yet a respectable liberal position, it is no longer a racist one.”

In that same interview, he even said that the Democratic Party should be more like one of America’s most infamous racists on issues of “common sense,” like crime and punishment, an issue on which Biden has always been right-wing. “I think the Democratic Party could stand a liberal George Wallace,” Biden told the Inquirer. “Someone who’s not afraid to stand up and offend people, someone who wouldn’t pander, but would say what the American people know in their gut is right.”

At the same time, Biden reiterated his support for civil rights overall—just not the major civil rights fight of the era—and his connections in Wilmington’s black community. “I still walk down the street in the black side of town,” he told the Washington Post in September 1975, “and you get—maybe they’re my clients—Mousey and Chops and all the boys at 13th and—I can walk in those pool halls, and I quite frankly don’t know another white man involved in Delaware politics who can do that kind of thing.”

Biden’s rise as an anti-busing leader came at the same time that busing was becoming a bigger and bigger issue in his home state. In 1974 and 1975, the federal courts ordered the state to come up with a plan to desegregate Wilmington schools. The latter ruling found that the state was violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

And Biden’s zeal for anti-busing didn’t end with Jimmy Carter’s election as president. As HuffPost wrote last week, Biden was the only senator to vote against two black men nominated for roles in the Justice Department, civil rights division head Drew Days III and solicitor general Wade McCree, specifically because they wouldn’t commit to opposing busing. Afterwards, Biden’s relationship with the Carter administration on the issue essentially broke down.

He also began making deeply suspect arguments about the nature of segregation itself. During one 1977 Senate debate on an anti-busing amendment he’d written with Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton, Biden said that the difference between segregation in the South and segregation in the North as one between “integrated neighborhoods and segregated facilities” versus “essentially integrated facilities and segregated neighborhoods,” which he described as a “consequence of normal migration patterns.” Redlining was as pervasive in Wilmington as it was anywhere else, but Biden maintained that his philosophical opposition was in “applying the same standard to two different ills.”

That amendment, which passed, barred the HEW department from using its only real tool to force schools to desegregate—the threat of pulling federal funding if they didn’t. It had an almost immediate effect: As the Morning News reported in May 1978, HEW informed a school superintendent in Ocala, FL, that “a complete remedy” to desegregate the district couldn’t be achieved “without transportation of some students to a school other than the one closest to home.” But because of Biden’s efforts, the agency told the superintendent, HEW couldn’t “require” that transportation to happen.

Here was a case in the South, in a place that clearly had trouble for years desegregating schools, in which the courts later found that segregation existed. In other words, it was exactly the sort of case where Biden earlier said he would have supported desegregation busing; his amendment, however, prevented HEW from making that happen.

“For my effort to restore a little common sense, a few of my colleagues pulled me aside to ask how and when ‘the racists had gotten to me,’” Biden wrote in his 2008 autobiography, Promises to Keep.

Meanwhile in Delaware, the courts continued to find that, contrary to what Biden thought, schools were segregated. In January 1978, a federal judge issued a court-ordered desegregation plan for Delaware which mandated that city students be bussed out to the suburbs for nine years, while suburban students be bussed into the city for three, and which merged the city school district with 10 suburban ones. New Castle County teachers went on a five-week strike over the disparities in pay between the old and new districts.

The plan was set to go into effect just as Biden’s re-election campaign was heating up. An amendment offered by Biden and Roth around that time, rehashing a failed attempt from 1976, would have restricted federal courts from ordering redistricting plans unless the discrimination was ruled to be intentional. It also would have stayed “all pending busing orders,” according to the Washington Post, including the Wilmington busing order. As CNN reported on Thursday, Biden even personally invited Sen. Eastland—who took the floor of the Senate not even a year after Germany surrendered in World War II to lambast black soldiers for their “utter dismal failure in combat in Europe” and accuse them of widespread rape of German women in Stuttgart, which he said proved “that the Negro race is most assuredly an inferior race”—to speak on the floor in support of Biden and Roth’s amendment.

According to the Congressional Record, Eastland never spoke and was absent the week the vote took place. His fellow segregationist Strom Thurmond, however, did speak in favor of the amendment. Thurmond echoed Biden’s arguments that Brown had been “misinterpreted” by the federal courts, arguing that “sociologists in this country have advocated positions that are not truly representative of the thinking of a majority of the American people,” and “that in many cases, the goal of gaining a racial mix becomes primary, and the education of our children becomes secondary.”

“I want to commend the Senators from Delaware for bringing this amendment to the attention of the Senate,” Thurmond said. “This is an important issue to all Americans and even though the Senate may not see fit to adopt this amendment today, it does provide the opportunity for debate on a matter of interest to not only the people of South Carolina, but the nation.”

Biden’s crusade to block court-enforced busing was a stark turn from his rhetoric about respecting the courts’ decisions on desegregation. In other words, when it came time to bring in the helicopters, Biden didn’t show up.

His bill with Roth was narrowly defeated a few weeks before the plan went into effect. “For my effort to restore a little common sense, a few of my colleagues pulled me aside to ask how and when ‘the racists had gotten to me,’” Biden wrote in his 2008 autobiography, Promises to Keep. One of his critics, he noted, included NAACP lobbyist and civil rights legend Clarence Mitchell.

In Promises to Keep, Biden acknowledged the political ramifications he was staring at back home, describing one train ride to D.C. in which he and longtime aide and future U.S. Sen. Ted Kaufman “convinced ourselves I could be beaten.” He recalled that Eastland and Georgia segregationist Sen. Herman Talmadge—who, as governor, called for closing schools in an attempt to stop integration—had advised him to “demagogue the shit out of the issue” in Delaware, advice Biden stressed that he declined. Later, Biden wrote that Eastland told him he’d come to Delaware to campaign for Biden. “I’ll campaign for ya or against ya, Joe,” Eastland told Biden, as recalled in Promises to Keep. “Whichever way you think helps you the most.”

The two Republicans who ran to replace him, hardline anti-busser James Venema and the more establishment candidate James Baxter, amazingly hit out at Biden for being too liberal on busing. Baxter won the primary, but Biden won the general comfortably.

Biden continued to support anti-busing measures even after he won re-election, but his prediction that the anti-busing liberals would protect the civil rights movement from being “kicked in the teeth” was proved wrong. The Reagan administration abandoned busing as a tool for desegregation almost immediately, and unapologetic segregationists like Helms and Thurmond became the anti-busing leaders in Congress.

Biden has continued to slam busing throughout his career, calling it a “liberal trainwreck” that was “tearing people apart” in his autobiography. But while the issue was of course controversial at the time, it’s clear now that in the wake of the courts and the federal government abandoning school integration as a conscious decision, schools have re-segregated. As Will Stancil noted for the Atlantic last year, the number of segregated schools doubled between 1996 and 2016, with over 70 percent of black children attending a segregated school.

That impact has been felt in Delaware, too. In 1981, the state legislature split the Wilmington school district into four. In 1996, the 1978 court order requiring Delaware to integrate its schools was lifted; by 2014, Arielle Niemeyer of the UCLA Civil Rights Project found, “nearly 20% of Delaware’s black students, and about 11% of Delaware’s Latino students” were attending “intensely segregated schools with overlapping concentrations of poverty.”

We’ve reached out to the Biden Foundation with a list of questions about his busing stance; we’ll update if and when we receive a response.

But after the Washington Post uncovered a long-forgotten 1975 interview with a defunct Delaware weekly newspaper last month, in which Biden forcefully argued against busing and appeared to advocate for a “separate but equal” approach to education, spokesperson Bill Russo defended his record, continuing to argue that busing was a bad move. “He never thought busing was the best way to integrate schools in Delaware—a position which most people now agree with,” Russo said. “As he said during those many years of debate, busing would not achieve equal opportunity. And it didn’t.” (In statements to both CNN and the Post, Russo said Biden was “one of the strongest and most powerful voices for civil rights in America.”)

What this bluntly means, of course, is that he places a premium on his ability to navigate the forces of white reaction to a changing society. In the 1970s, he did that by joining forces with racists […]

While the legacy of busing remains a controversial topic, however, it isn’t nearly as cut and dry as Russo claims. As Syracuse professor George Theoharis wrote for the Washington Post in 2015, the era of desegregation or “forced” busing, as Biden referred to it, produced narrower racial achievement gaps in American schools than we’ve seen since it ended. He also cited a 2010 study which “found that the level of integration was the only school characteristic (vs. safety and community commitment to math) that significantly affected students’ learning growth.”

“We need to be sober about our history,” Theoharis wrote. “Busing didn’t fail; the nation’s resolve and commitment to equal and excellent desegregated schools did.”

Aside from the negative impact on students’ education and socialization that retreating from desegregation had, the fact remains that on one of the most important civil rights battles of his early career, Biden allied himself with segregationists—the likes of Helms, Eastland, Thurmond—against civil rights crusaders both inside and outside of Congress.

Despite Biden’s fierce opposition to busing, he has continued to enjoy the support of civil rights leaders in Delaware. After his selection as then Sen. Barack Obama’s running mate in 2008, the New York Times quoted longtime Delaware civil rights leader Littleton P. Mitchell on Biden as saying, “He has adequately represented our community for many years, but he quivered that one time on busing.” (Mitchell died in 2009.) And in response to last month’s Post story, Biden’s office sent the outlet a statement from former Leadership Conference on Civil Rights head (and former Brooke staffer) Ralph Neas saying, “We disagreed on busing…but I always looked to Biden as a leader in the field of civil rights in other critical areas.”

Taken altogether, Biden’s approach to busing highlights the fact that he’s been a bellwether for national politics since the 1970s. And so it raises questions about how Biden will deal with civil rights battles of the current day, such as America’s inhumane immigration system—an issue on which the administration he served under has come under fierce criticism even from fellow Democrats—or, yes, the resegregation of schools that’s followed the retreat of the courts and federal government from the principle of integration.

More broadly, though, the thread that connects Biden’s busing record to his likely current run is his supposed standing—both implicit and explicitly stated—as a man who can “connect” to “ordinary” white people. What this bluntly means, of course, is that he places a premium on his ability to navigate the forces of white reaction to a changing society. In the 1970s, he did that by joining forces with racists, and there is little to suggest that his concept of politics has changed substantially since then. That makes it all the more troubling to imagine how that instinct might guide him now, when white backlash is spiking at such incendiary levels.

Although the forces to his left in 2019 aren’t quite exactly the same as they were when he began his political career, they are more socially and racially conscious than the “new kind of liberalism” Biden proudly described himself as adhering to in the 1975 Inquirer profile.

“Maybe we have less faith in human nature,” he admitted. “But we are beginning to question the ability of government to fundamentally alter human nature.”